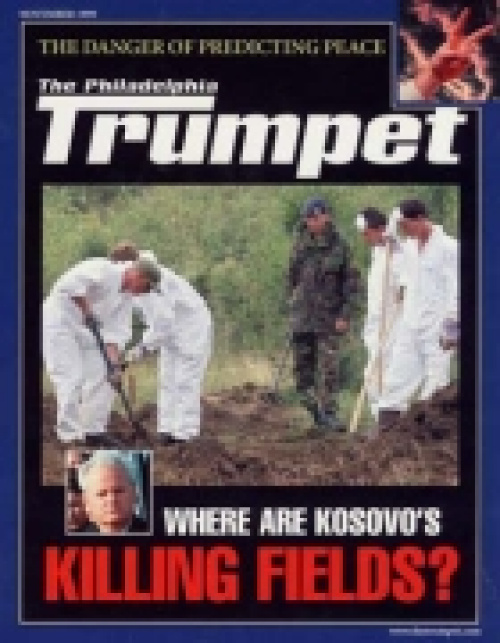

Where Are Kosovo’s Killing Fields?

This article is reprinted by permission from Stratfor, Inc.

On October 11, the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Republic of Yugoslavia (icty) reported that the Trepca mines in Kosovo, where 700 murdered ethnic Albanians were reportedly hidden, in fact contained no bodies whatsoever.

Three days later, the U.S. Defense Department released its review of the Kosovo conflict, saying that nato’s war was a reaction to the ethnic cleansing campaign by Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic. His campaign was “a brutal means to end the crisis on his terms by expelling and killing ethnic Albanians, overtaxing bordering nations’ infrastructures, and fracturing the nato alliance.”

The finding by The Hague’s investigators and the assertion by the Pentagon raise an important question. Four months after the war and the introduction of forensic teams from many countries, precisely how many bodies of murdered ethnic Albanians have been found? This is not an exercise in the macabre, but a reasonable question, given the explicit aims of nato in the war, and the claims the alliance made on the magnitude of Serbian war crimes. Indeed, the central justification for war was that only intervention would prevent the slaughter of Kosovo’s ethnic Albanian population.

On March 22, British Prime Minister Tony Blair told the House of Commons, “We must act to save thousands of innocent men, women and children from humanitarian catastrophe, from death, barbarism and ethnic cleansing by a brutal dictatorship.” The next day, as the air war began, President Clinton stated, “What we are trying to do is to limit his [Milosevic’s] ability to win a military victory and engage in ethnic cleansing and slaughter innocent people and to do everything we can to induce him to take this peace agreement.”

As nato’s first intervention in a sovereign nation, the war in Kosovo required considerable justification. Throughout the year, nato officials built their case, first calling the situation in Kosovo “ethnic cleansing,” and then “genocide.” In March, State Department spokesman James Rubin told reporters that nato did not need to prove that the Serbs were carrying out a policy of genocide because it was clear that crimes against humanity were being committed. But just after the war in June, President Bill Clinton again invoked the term, saying, “nato stopped deliberate, systematic efforts at ethnic cleansing and genocide.”

The Claims Grow

Indeed, as the months progressed, the estimates of those killed by a concerted Serb campaign, dubbed Operation Horseshoe, have swollen. Early on, experts systematically generated what appeared to be sober and conservative estimates of the dead. For example, prior to the outbreak of war, independent experts reported that approximately 2,500 Kosovar Albanians had been killed in the Serbian ethnic cleansing campaign.

That number grew during and after the war. Early in the campaign, huge claims arose about the number of ethnic Albanian men feared missing and presumed dead. The fog and passion of war can explain this. But by June 17, just before the end of the war, British Foreign Office Minister Geoff Hoon reportedly said, “According to the reports we have gathered, mostly from the refugees, it appears that around 10,000 people have been killed in more than 100 massacres.” He further clarified that these 10,000 were ethnic Albanians killed by Serbs.

On August 2, the number jumped up by another 1000 when Bernard Kouchner, the United Nations’ chief administrator in Kosovo, said that about 11,000 bodies had already been found in common graves throughout Kosovo. He said his source for this information was the icty. But the icty said that it had not provided this information. To this day, the source of Kouchner’s estimates remains unclear. However, that number of about 10,000 ethnic Albanians dead at the hands of the Serbs remains the basic, accepted number, or at least the last official word on the scope of the atrocities.

Regardless of the precise genesis of the numbers, there is no question that nato leaders argued that the war was not merely justified, but morally obligatory. If the Serbs were not committing genocide in the technical sense, they were certainly guilty of mass murder on an order of magnitude not seen in Europe since Nazi Germany. The Yugoslav government consistently denied that mass murder was taking place, arguing that the Kosovo Liberation Army (kla) was fabricating claims of mass murder in order to justify nato intervention and the secession of Kosovo from Serbia. Nato rejected Belgrade’s argument out of hand.

Thus, the question of the truth or falsehood of the claims of mass murder is much more than a matter of merely historical interest. It cuts to the heart of the war—and nato’s current peacekeeping mission in Kosovo. Certainly, there was a massive movement of Albanian refugees, but that alone was not the alliance’s justification for war. The justification was that the Yugoslav army and paramilitaries were carrying out Operation Horseshoe, and that the war would cut short this operation.

But the aftermath of the war has brought precious little evidence, despite the entry of Western forensics teams searching for evidence of war crimes. Mass murder is difficult to hide. One need only think of the entry of outsiders into Nazi Germany, Cambodia or Rwanda to understand that the death of thousands of people leaves massive and undeniable evidence. Given that many nato leaders were under attack at home—particularly in Europe—for having waged the war, the alliance could have seized upon continual and graphic evidence of the killing fields of Kosovo to demonstrate the necessity of the war and undercut critics. Indeed, such evidence would help the alliance undermine Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic, by helping to destroying his domestic support and energizing his opponents.

As important, no one appears to really be trying to recover all of the Kosovo war’s reported victims. Of the eight human rights organizations most prominent in Kosovo, none is specifically tasked with recovering victims and determining the cause of death. These groups instead are interviewing refugees and survivors to obtain testimony on human rights violations, sanitizing wells and providing mental health services to survivors. All of this is important work. But it is not the recovery and counting of bodies.

It is important to note that a sizable number of people who resided in Kosovo before the war are now said to be unaccounted for—17,000, according to U.S. officials. However, the methodology for arriving at this number is unclear. According to nato, many records were destroyed by the Serbs. Certainly, no census has been conducted in Kosovo since the end of the war. Thus, it is completely unclear where the specific number of 17,000 comes from. There are undoubtedly many missing, but it is unclear whether these people are dead, in Serbian prisons—official estimates vary widely—or whether they have taken refuge in other countries.

The Investigation

The dead, however, have not turned up in the way that the West anticipated, at least not yet. The massive Trepca mines have so far yielded nothing. Most of the dead have turned up in small numbers in the most rural parts of Kosovo, often in wells. News reports say that the largest grave sites have contained a few dozen victims; some officials say the largest site contained far more, approximately 100 bodies. But the bodies are generally being found in very small numbers—far smaller than encountered after the Bosnian war.

Only one effort now under way may shed light on just how many ethnic Albanian civilians were—or weren’t—killed by Serb forces. The icty is coordinating efforts to investigate war crimes in Kosovo. Like human rights organizations, the tribunal’s primary aim is not to find all the reported dead. Instead, its investigators are gathering evidence to prosecute war criminals for four offenses: grave breaches of the Geneva Convention, violations of the laws of war, and genocide and crimes against humanity. The tribunal believes that it will, however, be able to produce an accurate death count in the future, although it will not say when. A progress report may be released in late October, according to tribunal spokesman Paul Risley.

Under the tribunal’s guidance, police and medical forensic teams from most nato countries and some neutral nations are assigned to investigate certain sites. The teams have come from 15 nations: Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States. The United States has sent the largest team, with 62 members. Belgium, Germany and the United Kingdom have each sent teams of approximately 20. Most countries dispatched teams of fewer than 10 members.

So far, investigators are a little more than one quarter of the way through their field work, having examined about 150 of 400 suspected sites. The investigative process is as follows: icty investigators follow up on reports from refugees or kfor troops to confirm the existence of sites. Then the tribunal deploys each team to a certain region and indicates the sites to be investigated. Sites are either mass graves—which according to the tribunal means that more than one body is in the grave—or crime scenes, which contain other evidence. The teams exhume the bodies, count them, and perform autopsies to determine age, gender, cause of death and time of death all for the purpose of compiling evidence for future war crimes trials. The by-product of this work, then, is the actual number of bodies recovered. The investigations will continue next year when the weather allows further exhumations.

In the absence of an official tally of bodies found by the teams, we are forced to piece together anecdotal evidence to get a picture of what actually happened in Kosovo. From this evidence, it is clear that the teams are not finding large numbers of dead, nothing to substantiate claims of “genocide.”

The fbi’s work is a good example. With the biggest effort, the bureau has conducted two separate investigations, one in June and one in August, and will probably be called back again. In its most recent visit, the fbi found 124 bodies in the British sector of Kosovo, according to fbi spokesman Dave Miller. Almost all the victims were killed by a gunshot wound to the head or blunt force trauma to the head. The victims’ ages were between 4 and 94. Most of the victims appeared to have been killed in March and April. In its two trips to Kosovo since the war’s end, the FBI has found a total of 30 sites containing almost 200 bodies.

The Spanish team was told to prepare for the worst, as it was going into Kosovo’s real killing fields. It was told to prepare for over 2,000 autopsies. But the team’s findings fell far short of those expectations. It found no mass graves and only 187 bodies, all buried in individual graves. The Spanish team’s chief inspector compared Kosovo to Rwanda. “In the former Yugoslavia crimes were committed, some no doubt horrible, but they derived from the war,” Juan Lopez Palafox was quoted as saying in the newspaper El Pais. “In Rwanda we saw 450 corpses [at one site] of women and children, one on top of another, all with their heads broken open.”

In Kosovo, bodies are simply not where they were reported to be. For example, in July a mass grave believed to contain some 350 bodies in Ljubenic, near Pec—an area of concerted fighting—reportedly contained only seven bodies after the exhumation was complete. There have been similar cases on a smaller scale, with initial claims of 10 to 50 buried bodies proven false.

Investigators have frequently gone to reported killing sites only to find no bodies. In Djacovica, town officials claimed that 100 ethnic Albanians had been murdered but reportedly alleged that Serbs had returned in the middle of the night, dug up the bodies, and carried them away. In Pusto Selo, villagers reported that 106 men were captured and killed by Serbs at the end of March. nato even released satellite imagery of what appeared to be numerous graves, but again no bodies were found at the site. Villagers claimed that Serbian forces came back and removed the bodies. In Izbica, refugees reported that 150 ethnic Albanians were killed in March. Again, their bodies are nowhere to be found. Ninety-six men from Klina vanished in April; their bodies have yet to be located. Eighty-two men were reportedly killed in Kraljan, but investigators have yet to find one of their bodies.

What Happened?

Killings and brutality certainly took place, and it is possible that massive new findings will someday be uncovered. Without being privy to the details of each investigation on the ground in Kosovo, it is possible only to voice suspicion and not conclusive proof. However, our own research and survey of officials indicates that the numbers of dead so far are in the hundreds, not the thousands. It is possible that huge, new graves await to be discovered. But ethnic Albanians in Kosovo are presumably quick to reveal the biggest sites in the hope of recovering family members or at least finding out what happened. In addition, large sites would have the most witnesses, evidence and visibility for inspection teams. Given progress to date, it seems difficult to believe that the 10,000 claimed at the end of the war will be found. The killing of ethnic Albanian civilians appears to be orders of magnitude below the claims of nato, alliance governments and early media reports.

How could this have occurred? It appears that both governments and outside observers relied on sources controlled by the kla, both before and during the war. During the war this reliance was heightened; governments relied heavily on the accounts of refugees arriving in Albania and Macedonia, where the kla was an important conduit of information. The sophisticated public relations machine of the kla and the fog of war may have generated a perception that is now proving dubious.

What is clear is that no one is systematically collecting the numbers of the dead in Kosovo even though such work would only help nato in its efforts to remain in Kosovo and could possibly topple Milosevic. What can be learned of the investigations to date indicates deaths far below expectations. Finally, all of this suspicion can be easily dispelled by a comprehensive report by nato, the United Nations or the United States and other responsible governments detailing the findings of the forensic teams, and giving time frames for completion and results. It is unclear that, even if the icty releases a report soon, it will address all these issues. The lack of an interim report indicating the discovery of thousands of Albanian victims strikes us as decidedly odd. One would think that Clinton, Blair and the other leaders would be eager to demonstrate that the war was not only justified, but morally obligatory.

It really does matter how many were killed in Kosovo. The foreign policy and political implications are substantial. There is a line between oppression and mass murder. It is not a bright, shining one, but the distinction between hundreds of dead and tens of thousands is clear. The blurring of that line has serious implications not merely for nato’s integrity, but for the notion of sovereignty. If a handful—or a few dozen—people are killed in labor unrest, does the international community have the right to intervene by force? By the very rules that nato has set up, the magnitude of slaughter is critical.

Politically, the alliance depended heavily on the United States for information about the war. If the United States and nato were mistaken, then alliance governments that withstood heavy criticism, such as the Italian and German governments, may be in trouble. Confidence in both U.S. intelligence and leadership could decline sharply. Stung by scandal and questions about its foreign policy, the Clinton administration is already having difficulty influencing world events. That influence could fall further. There are many consequences if it turns out that nato’s claims about Serb atrocities were substantially false.