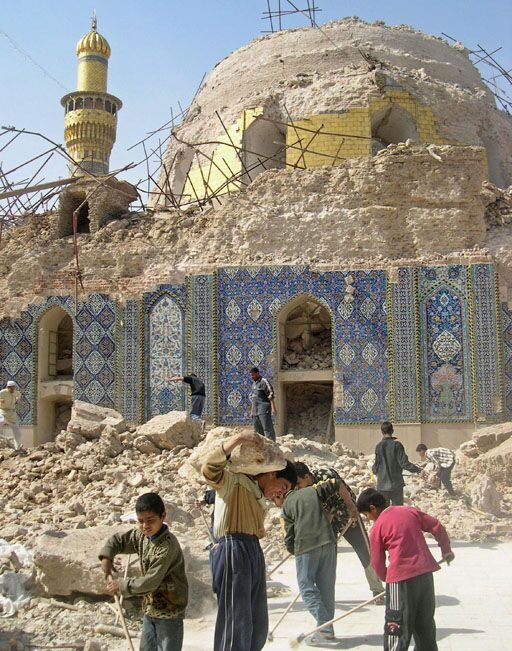

Behind Iraq’s Move Toward Civil War

Since the bombing last Wednesday of the Al-Askariyah shrine in Samarra—one of the most sacred Shiite mosques in Iraq—accusations have been flying. Many people immediately blamed Sunni insurgents. Iraq’s Shiite leadership and Tehran pointed the finger, indirectly, at Israel and the United States. A Tehran newspaper claimed it was a plot in continuation of the publication of the Mohammad cartoons. Jordanian lawmakers blamed firstly Israeli foreign intelligence agency Mossad, and then the Americans. The U.S. and various analysts are certain that it was either foreign jihadists or Iraqi extremists. Then there is the theory that it was actually the Shiites. After all, why did the explosion occur only minutes after all the Shiite worshipers had left after their morning prayers, avoiding numerous casualties that would normally be the aim of such an attack?

No one has come forward to claim responsibility, and there is no hard evidence of who was responsible. But it doesn’t really matter. The ongoing repercussions depend more on who various parties thought were the perpetrators—and how the various parties can use the attacks to their advantage.

Unsurprisingly for those watching Middle East events, it is Iran—and Iraq’s Shiites—that is likely to profit the most from the attacks. And, as the Australian newspaper stated, “Of all the involved parties, it is perhaps the U.S. that shuddered most when the dust settled around the fallen dome” (February 25).

The attack on the Shiite shrine resulted in a wave of retaliatory violence directed toward Sunnis. Daytime curfews were imposed amid reports of imminent civil war. By Saturday, and about 200 deaths later, attacks had abated somewhat, but the sectarian violence continues.

This is certainly not the first time the Shiites have been severely provoked. Since 2003 there have been numerous attacks on Shiite mosques, religious gatherings and other Shiite targets; several high-level Shiite leaders have even been assassinated. None of these incidents, however, resulted in retribution from the Shiites on any level approaching that of the past week.

So why, this time around, has the response been so swift and so violent?

It appears that it has been timed to send a message, primarily to the U.S.

The mosque attack came amid some difficult negotiations to form a “national unity” coalition government; and at a time of particular tension between the Shiite leadership and the U.S.—both of these issues being intertwined.

In the parliamentary election on December 15 to select a 275-seat Council of Representatives, the Shiites maintained a majority. Shia parties won 128 seats, followed by the Kurds and then the Sunnis with the smallest representation among the three ethnic groups. This just left the task of establishing a “national unity” leadership to the satisfaction of all parties, particularly the Sunnis, who were feeling shortchanged. But the Shiites—and more importantly, their sponsor Iran—were not about to give up any of their power easily.

The U.S. had strong motivation to limit Shiite control to the benefit of the Sunnis. The idea was to get the Sunnis involved in the government and keep them happy so Sunni leadership could help keep a lid on the ongoing insurgency. But it was more than that: Without the Sunnis in a political position to check the Shiites, Iran would gain unparalleled influence over Iraq. And that, it seems, is what the U.S. may be coming to realize is the bigger danger.

This situation escalated to the point where “[t]he United States and the Iraqi Shia [were] publicly clashing over the extent to which the Shia will control Iraq once its full-term government is formed” (Stratfor, February 21). The tussling between U.S. officials and Shiite leaders shows how determined Iraq’s Shiites are to hold as much control as possible in the new government.

In this respect, the Shiites have been on the defensive.

Now, Stratfor insists, “they now are using the attack on the shrine to regain the initiative and consolidate their hold on power in Baghdad“ (February 23, emphasis ours).

No matter who was actually responsible for the mosque attack, the Shiites can use this situation to acquire more power by undermining the Sunnis’ position in political negotiations. “Leveraging the street power of the Iraqi majority, the Shia can make the argument that they have been targets of sectarian violence for far too long and are nearing the end of their patience” (ibid.).

In all this, it appears Iran will be the big winner. The situation surrounding the shrine attack gave Iran an ideal opportunity to remind the U.S., once again, of the cards it holds.

Following the bombing, Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei issued a statement placing blame on Israel and the U.S. and urging Shiites not to retaliate. This, said Stratfor, “sent a very clear signal that the Iranians have it in their power to create a living hell for the Bush administration in Iraq” (ibid.).

Abdel-Aziz al-Hakim, head of the Shiite United Iraqi Alliance, which dominates Iraq’s government, stated that the U.S. ambassador must share some of the blame for the attack because of statements he had made.

These statements by senior Shiite leaders of both Iran and Iraq, together with the fear of civil war the attack and its aftermath sparked, aimed to send a message to the U.S.: that they still have control over the Shiite majority of the Iraqi street.

The whole situation surrounding the shrine bombing is simply a demonstration of the increasing power Iran holds in the region as its end-time prophetic status becomes evermore apparent.

Peter Galbraith, a former U.S. envoy, wrote in the New York Review of Books that the main beneficiary of America’s efforts in Iraq, Israel-Palestine, Syria and Egypt, was an emboldened Iran. “Democracy in Iraq brought to power Iran’s allies who are in a position to ignite an uprising against American troops that would make current problems with the Sunni insurgency seem insignificant,” Galbraith wrote. “Iran in effect holds the U.S. hostage in Iraq and as a consequence we have no good military or non-military options in dealing with Iran’s nuclear facilities” (Guardian, London, February 24).

In November 2003, the Trumpet wrote about this very situation in the article “Is America Empowering Iran?” In fact, editor in chief Gerald Flurry has been writing about the rise of Iran for over a decade.

We are now seeing before our eyes Iran‘s takeover of Iraq and the formation of the king of the south—an Islamic power bloc that features greatly in end-time Bible prophecy.