150 Years of Lasting Impressions

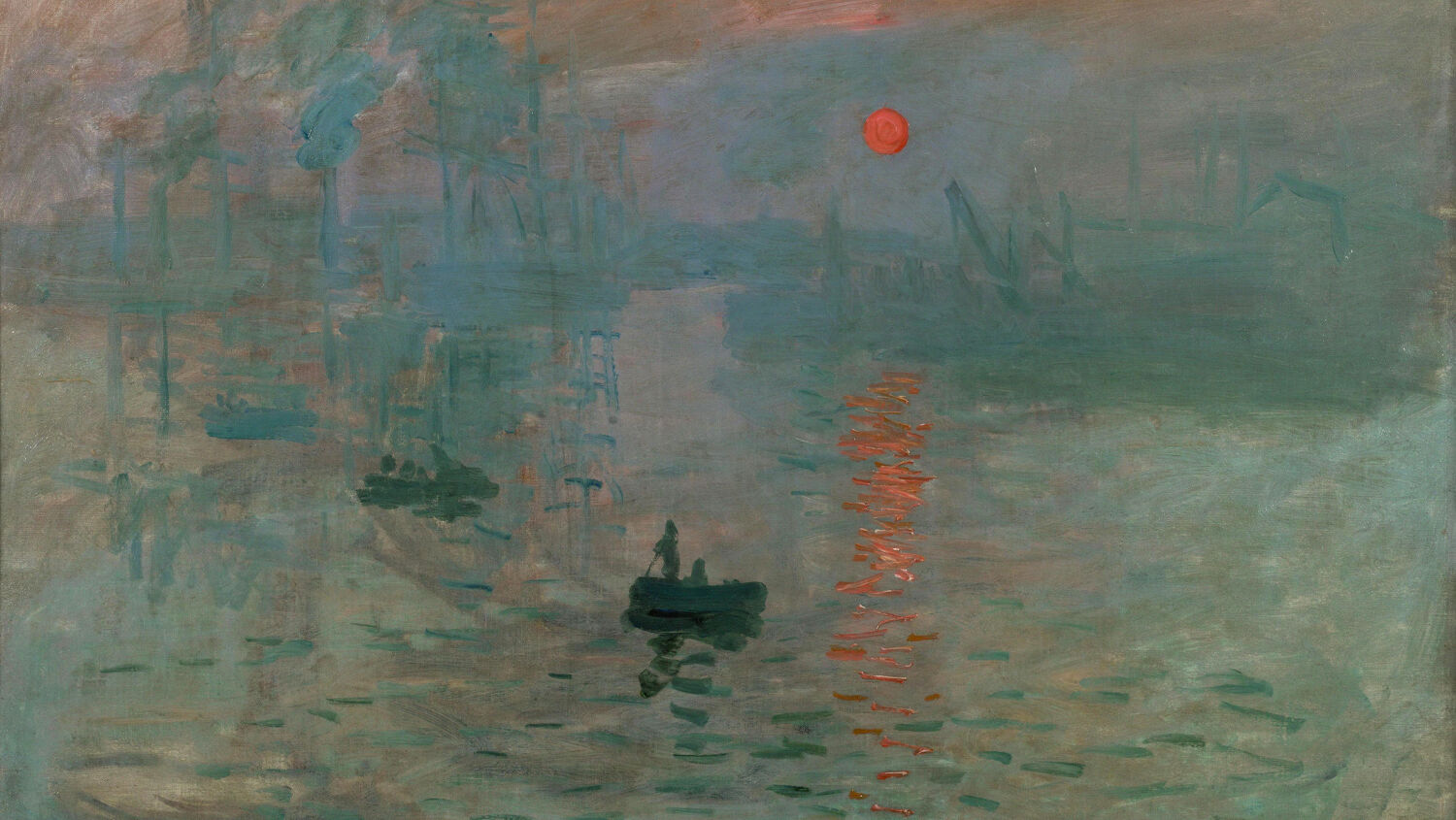

You awake to a commotion of industrial activity outside your hotel room window in the city of Le Havre on France’s northern coast. The year is 1872, and the noise compels you to investigate. Peering out your window, you notice the orange orb of the sun piercing through the thick mist that has enveloped the harbor. Across the harbor, you see the faint silhouettes of factory smokestacks, their plumes contributing to the poor visibility. The dark outline of a ship almost blends in with the smokestacks. A few dinghies bob in the foreground, rocking side to side on the uneven sea.

This is the feeling given by the painting Impression, Sunrise, by Claude Monet. Impression, Sunrise was one of many paintings at the 1874 exhibition of the “Cooperative and Anonymous Association of Painters, Sculptors and Engravers” in Paris, France.

Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, Paul Cézanne and other household names of the art world assembled at the exhibition to showcase their (what many then considered) unconventional art. Today, we know their art movement as “impressionism.” The name came from Impression, Sunrise, when Louis Leroy, an art critic at the 1874 event, gave the label to the whole group.

Art lovers the world over today are celebrating the 150th anniversary of what Leroy called the “First Impressionist Exhibition.” Paris’s grand Musée d’Orsay has gathered roughly 130 of the paintings from that original showcase in a special exhibition. Those paintings will travel to Washington, D.C.’s, National Gallery of Art later this year. Auctioneering giants Sotheby’s and Christie’s celebrated the anniversary with specialized auctions.

People will pay millions of dollars for a canvas splashed with oil paint. Millions fly to Europe every year to ogle canvases in museums. We classify prominent artists among statesmen, writers and other greats of civilization. The question is: why? Why do people view art as influential and beloved? Why do we value art as part of our common human culture?

This painting tradition started in the Middle Ages. The Catholic Church needed artists to depict saints and madonnas on altarpieces, frescos and other religious art. This “gothic period” of art history is most famous for two-dimensional “holy men” with hypnotic stares on a gold background.

But as the West moved into the 1300s, something interesting happened to those paintings. Instead of a nebulous golden “heaven,” backgrounds started to feature blue skies, rocks, trees and animals. Artists added the illusion of depth. The people became more lifelike, with realistic clothing and skin tones. Artists were learning that their work didn’t have to be generic. Their art could express their imagination.

The Renaissance advanced. Religious art was still plenteous, but art was no longer exclusively the domain of the church. Bigwigs paid big money for realistic self-portraits. Artists used themselves as models. They used the brush and canvas to depict scenes from history, the Bible or local proverbs. Some used art as a medium for a political message: Catholic versus Protestant, freedom versus tyranny, order versus anarchy.

Politics, storytelling, how we view ourselves—these are all aspects of our fundamental humanity. Most notable of all, for the purpose of this article, is creativity. This implies more than the ability to put something together that didn’t exist before. This implies being able to step back and appreciate what one put together. And it implies that somebody other than the creator can appreciate the work for the same reasons.

As for the impressionists, they created their unique style after rejecting “academicism”—realistic paintings of Greco-Roman historical or mythological subjects. Instead, they focused on everyday scenes, manipulating color, texture and other factors to make fuzzy but discernible “impressions.”

There may have been a bit of rebellion in the impressionists’ motives, but that doesn’t mean their works are to be rejected. Other areas of Western culture, like the eras of fine arts music tradition, developed because creators thought outside the box and did something different from their predecessors. Breaking the confines of arbitrary criteria isn’t necessarily a bad thing. If anything, the impressionists’ revolutionary approach demonstrates the human mind’s capacity to create beauty where none was before, to push the boundaries of imagination.

That doesn’t mean everything considered art is worthwhile. And it doesn’t mean everything the impressionists produced led to good. The impressionists were flawed men like us all. And their views that art didn’t have to be realistic eventually evolved into bizarre modern and contemporary works that some call “art.”

But art creation and appreciation point to a higher truth worth pondering.

“Your ability to be inspired by a symphony, to be enriched by a sculpture, or to be uplifted by a sunset is a miracle,” Ryan Malone writes in How God Values Music. “That ability is possible because of the God-like mind that God created in you.”

God said in Genesis 1:26, right before Adam’s creation: “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness ….” Gesenius’ Hebrew-Chaldee Lexicon defines the world “image” as “a shadow.” Strong’s Concordance states it comes “from an unused root meaning to shade; [meaning] resemblance.” In other words, man was designed to reflect God.

God desires to build His character in us. But this “reflection” of God includes our mental faculties. “[H]uman minds were made to function in the same manner as the Creator’s, although in an inferior way,” Herbert W. Armstrong wrote in The Incredible Human Potential. “But how do we humans use our minds? We are endowed with something akin to creative powers.”

“This ability makes the human being a unique creation,” Mr. Malone writes. “No animal has this ability. God gave it only to man because of our unique and special purpose. A feature of the unique, God-like mind that humans possess is the ability to appreciate creative, artistic endeavors.”

Think about the first verse in the Bible: “In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth” (Genesis 1:1). Before God could create the heavens and the Earth, He had a concept of what those things would look like in His mind. He had to imagine creation when there was no creation to base it from. Everything we see in the natural world is a product of God’s creative imagination. And what did God do after He formed the world? “And God saw every thing that he had made, and, behold, it was very good” (verse 31). He sat back, beheld the works of His hands, and appreciated them.

Like everything man apart from God has touched, one can find much perversion in the art world. But through using our minds to create and appreciate truly fine art, we can learn to think more like God.

This makes the 150th anniversary of the First Impressionist Exhibition worth celebrating.

If you would like to learn more about how fine culture can connect us with God, request a free copy of How God Values Music.