Exoplanets and the Search for Earth 2.0

Exoplanets and the Search for Earth 2.0

“My very educated mother just served us noodles.” That’s a popular mnemonic device used for remembering the planets Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. Or if you learned it before Pluto’s career setback in 2006, it may instead have been “nine pizzas” that your bookish mom dished up. In either case, these are the planets most of us have studied and have perhaps observed with the naked eye or a science teacher’s telescope.

But these are only the planets floating around one midsize star in one quiet neighborhood of one average-size galaxy. There is a considerable amount of space out there. And today an array of powerful space and ground telescopes enable us to gaze deeply into it, including Hubble, Spitzer, Gaia, Trappist-South, Kepler, Nustar, the James Webb Space Telescope and the imaginatively named Very Large Telescope, which is soon to be outshone by the equally imaginatively named Extremely Large Telescope.

These celestial magnifiers let us see much farther out with far greater clarity. And they have shown us that the handful of celestial orbs in our solar system are only the smallest beginning. We are finding that planets are everywhere.

Exoplanet is the term used for any planet outside our solar system, and the first of them was discovered in 1992. And actually, it wasn’t just one but two: Phobetor and Poltergeist. These sibling spheres rocked the world of astronomy when they were found orbiting a pulsar in the constellation Virgo, some 2,300 light-years away from our Blue Marble.

Since then, stargazing technology has continued to dramatically improve and so have planet-finding techniques, such as stellar wobble, direct imaging, microlensing and the transit method. Combining the increasingly penetrating range of telescopes with this increasingly effective assortment of methods, astronomers have now confirmed the existence of thousands of exoplanets. As of June 18, the count is up to 6,140.

Weirdly Wonderful Worlds

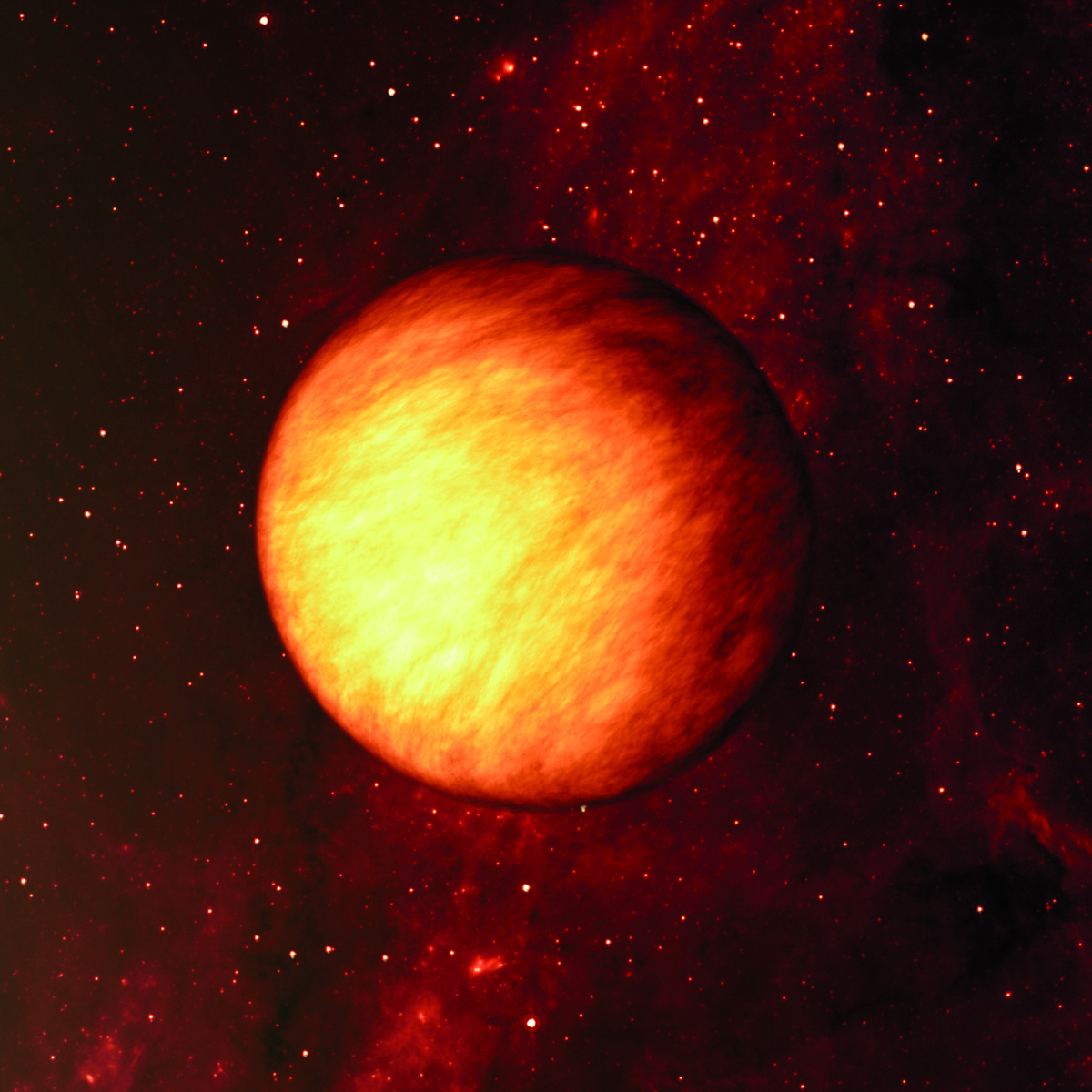

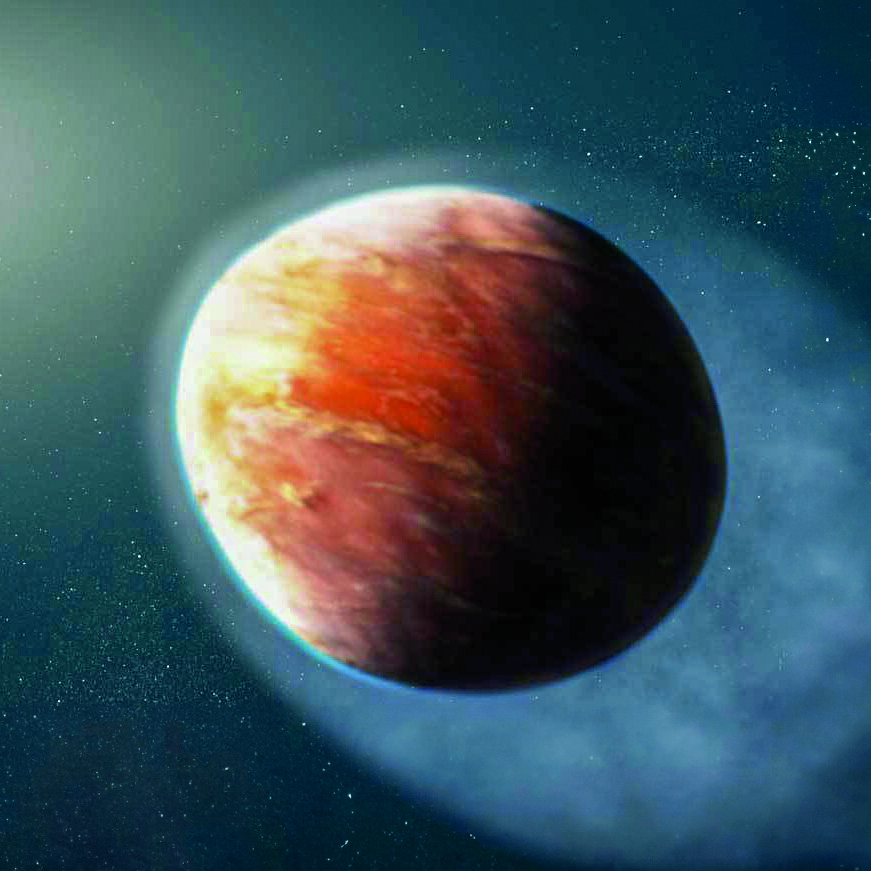

Many of the exoplanets that have been confirmed so far are comparable to the worlds in our solar system, not terribly unlike Neptune, Jupiter or Venus. But some are as surreal and weirdly wonderful as anything from a Star Trek episode or an Isaac Asimov novel—or more so.

“We have found planets of almost every type,” said Hubble Space Telescope project scientist Kenneth Carpenter. “We may actually be in a situation where reality is more strange than the fictional predictions.”

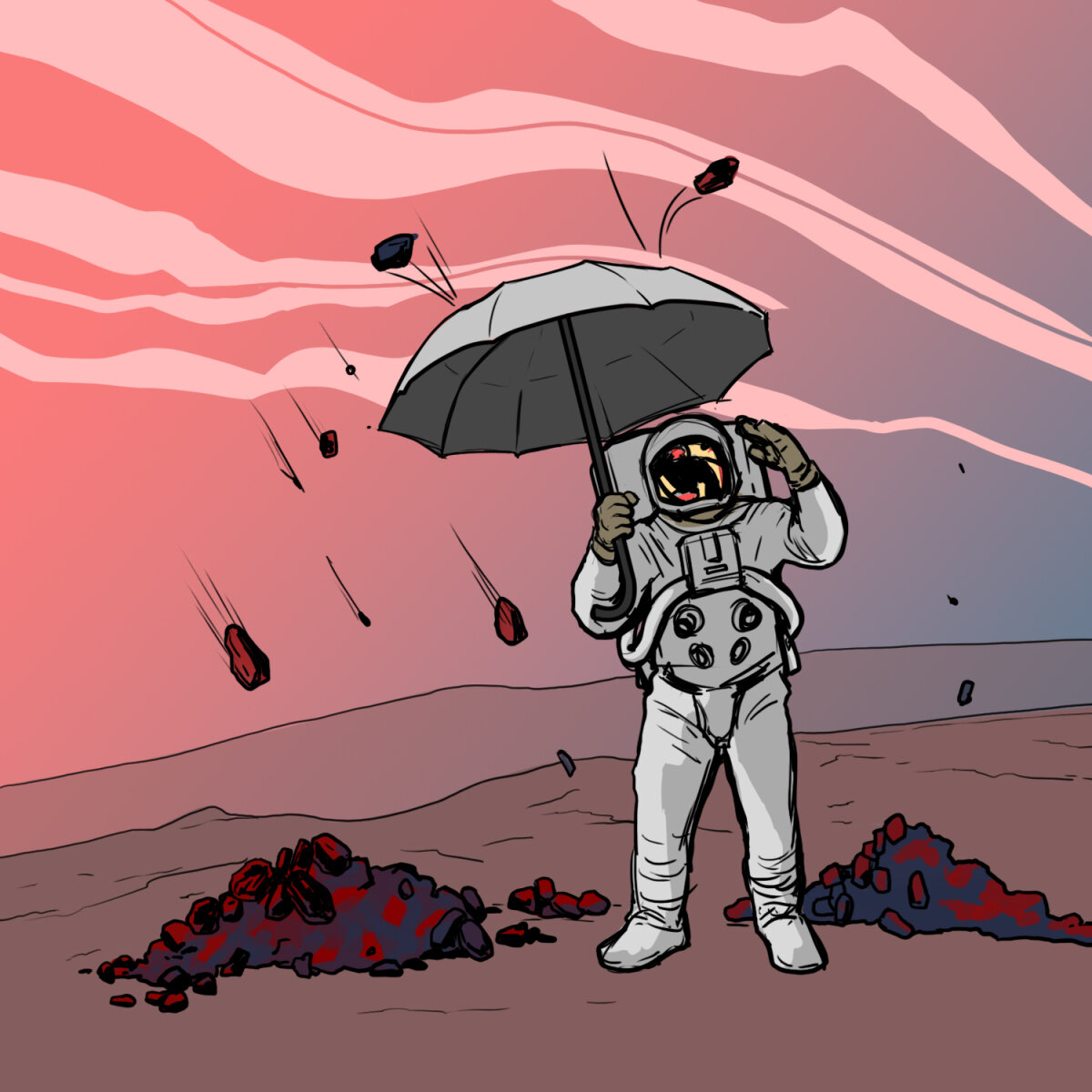

Astronomers have discovered ocean worlds, where deep waters cover every inch of the land. If that’s too tame for you, we have also found an exoplanet called Kepler-78b that is covered completely by oceans of lava. Then there is wasp-121b where weather conditions cause rubies and sapphires to rain down lavishly from the skies. We’ve found some that are “tidally locked,” with one half always blistering under their star and the other half freezing in unending darkness. And we have found at least two planets that are not spherical but egg-shaped, since they orbit their host stars so closely that the gravity ovals them. There are also exoplanets that orbit more than one star, some that orbit dead stars, and even “rogue planets” that are so freewheeling that they don’t orbit any star at all.

The details of the 6,140 confirmed exoplanets are tantalizing stargazers and stretching imaginations into a constellation of new directions. But even these thousands are just the start. Astronomers estimate that the Milky Way alone holds 100 to 200 billion exoplanets. And if you’re talking about the whole universe, the number grows to a size we can’t yet really even estimate. “With hundreds of billions of galaxies, the universe likely teems with many trillions of stars,” science journalist Elisha Sauers writes. “And if most stars have one or more planets around them, that’s an unfathomable number of worlds.”

The vast numbers of exoplanets have astronomers excited beyond words. And the most exciting of all are those that are earthlike, with the right proximity to a star, and with size, mass, elemental composition and potential atmosphere and water cycles that could possibly work together to sustain life.

Earth 2.0?

One somewhat earthlike exoplanet, called Gliese 667Cc, lies just 22 light-years from us. It has years that last a mere 28 Earth days. Were it orbiting a G-class star like our sun so closely, Gliese 667Cc would be far too hot. But its star is a red dwarf, far cooler than the sun. So distance and heat cancel out, placing this exoplanet in the habitable zone, or “Goldilocks Zone,” around its star, where it is neither too cold nor too hot to support carbon-based life. However, Gliese 667Cc is likely within striking distance of its star’s flares, which could make it far less—or not at all—life-friendly.

If you think a 28-day year is short, brace yourself for Proxima Centauri b. Its discovery in the habitable zone of its star electrified astronomers, since it lies only four light-years from us. But this exoplanet circles its star so closely that it is bombarded by extreme ultraviolet radiation. And that tight orbit means its year is only 11.2 days long, which could be lucrative for sellers of anniversary cards but overwhelming for tax-filing accountants and most other residents.

Another potentially earthlike exoplanet is Kepler-22b, 640 light-years away. Its 290-day year is not far off from Earth’s, and it orbits a G-class star like ours. But Kepler-22b’s star is considerably cooler and smaller than the one at the center of our solar system, which may turn a cold shoulder to life.

Kepler-186f is another exoplanet that may be capable of supporting life as we know it. It lies 580 light-years from us and is only about 10 percent larger than the third rock from the sun. But it receives only about a third as much energy from its host star as we do from ours, which hangs a large question mark over Kepler-186f’s ability to support a biosphere. As with many exoplanets, there are also lingering questions about what Kepler-186f is made of. Astronomer Phil Plait wrote, “It could be a barren rock, or a fecund water world, or made entirely of Styrofoam peanuts, or some weird thing we haven’t even imagined yet.”

The most earthlike exoplanets so far discovered are those orbiting a Jupiter-size red dwarf named Trappist-1, some 41 light-years away. Seven planets have been discovered in this star’s orbit, all of which appear to be rocky like Earth. Three of these are well within the Goldilocks Zone. Astrophysicists using the James Webb Space Telescope are over the moon about the Trappist-1 system because some of its exoplanets may have the same kind of secondary atmosphere as Earth and may have what it takes to support life. “There are only a handful of stellar systems where we have the opportunity to look for these sorts of atmospheres,” said Ward Howard, a Sagan Fellow at the University of Colorado–Boulder, who studies Trappist-1 and its satellites. “Each one of these planets is truly precious.”

More earthlike exoplanets are being discovered every month now, and many of them seem to have some promising circumstances. Yet Earth 2.0 remains elusive. And there is good reason to think that no matter how many exoplanets we discover, we will never find one that is a true Earth twin, a home to life.

‘Tohu and Bohu’ to Eden

The Bible shows that Earth itself was once in a condition somewhat like the desolate exoplanets we are now discovering. “And the earth was without form and void,” Genesis 1:2 states. God did not originally create it that way, but the great angelic rebellion described in such verses as Jude 6 reduced this precious planet to ruin.

These words “without form” and “void” are translated from the Hebrew words tohu and bohu, and could also be rendered “waste” and “empty.” That was the state of Earth when God determined to renew and restore it to a place of abundance where new beings, humans, could live (Psalm 104:30).

Transforming a planet from tohu and bohu into a thriving biosphere is no small feat. Genesis 1 lays out how God accomplished this dramatic restoration. The atmosphere was healed so the sun could once again energize and light the planet. The surface was restructured to separate dry land from ocean. The rotation was apparently altered. And plants, animals and people were created.

The Bible also has plenty to say about the vast universe beyond Earth. But it makes clear that, at present, there is no life on the other planets, whether here in our solar system or beyond. Romans 8:19-22 say the whole universe is presently in “bondage to decay” and figuratively “groaning” over its state of lifelessness and deterioration (Revised Standard Version).

The late educator Herbert W. Armstrong discussed these scriptures in his landmark book The Incredible Human Potential. “This passage indicates precisely what all astronomers and scientific evidence indicate—the suns are as balls of fire, giving out light and heat; but the planets, except for this Earth, are in a state of death, decay and futility ….”

If you read only that much of it, the cosmic situation would seem bleak—as if there were little reason to keep studying exoplanets and perhaps no real purpose for the vast universe. But there is much more to this passage. It states that the universe “will be set free” from its current condition (verse 21). Why would the universe need to be freed from its state of lifelessness and decay? Because, as we learn from Isaiah 45:18, God created the universe “not in vain,” but “to be inhabited.”

The Creator makes clear that it is not just Earth that He designed and made to be inhabited, but the universe! This means there are exoplanets that will undergo a process similar to the Genesis 1 restoration that Earth underwent.

Imagine the re-creation described in Genesis by the millions or even trillions. If a given planet isn’t in the Goldilocks Zone, maybe it will be nudged into a more benevolent orbit to undergo terraforming. In the case of those “rogue planets,” more than a nudge will be needed to lock them into the orbit of a good star. A planet that is tidally locked can be given a spin. Atmospheres will be created or repaired. Surfaces will be restructured. Entire planets will be retrofitted with water cycles. And intricate ecosystems will be designed and vivified. Some of this will be life as we know it. Much of it may well be trailblazing creations of life we don’t as yet know. Some may not even be carbon-based.

The Bible does not reveal the details of this future, universe-wide project of liberating the exoplanets from their current condition of lifelessness and decay. But it does tell us who will be carrying out this incredible work. Romans 8:21 reveals them to be “the children of God.”

That means us.

Connecting this with such passages as Psalm 8 and Hebrews 2, Mr. Armstrong explained: “[F]or those willing to believe what God says, He says that He has decreed the entire universe—with all its galaxies, its countless suns and planets—everything—will be put under man’s subjection. …

“When we (converted humans) are born of God—then having the power and glory of God—we are going to do as God did when this Earth had been laid ‘waste and empty’ …. [W]e shall impart life to billions and billions of dead planets, as life has been imparted to this Earth” (ibid).

Mr. Armstrong wrote a whole book and numerous articles on this topic and discussed it extensively because it is the meaning of life.

“Put together all these scriptures,” he wrote, “and you begin to grasp the incredible human potential. Our potential is to be born into the God Family, receiving total power! We are to be given jurisdiction over the entire universe!” (ibid).

The ongoing discovery and study of exoplanets is exciting beyond words, but not for the reason modern astronomers think. No matter how good the telescopes and planet-finding methods become, those who hope to find life on an exoplanet in this age will only be disappointed. But in the future when God begins the next phase of His plan for mankind, then untold billions or trillions or quadrillions of planets will become rife with life. The universe was made to be inhabited.