A New Sheriff in Tehran

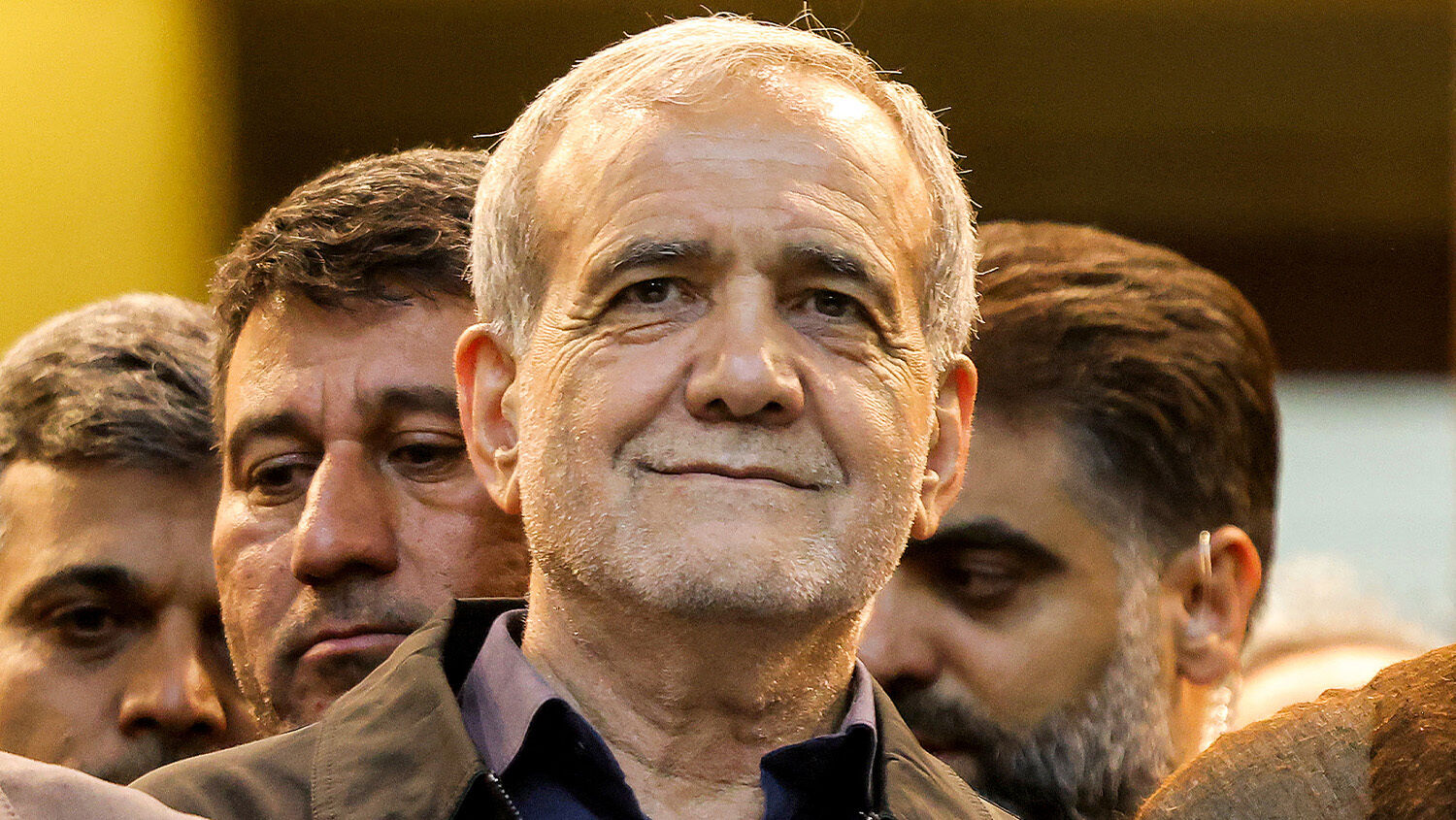

On July 5, Masoud Pezeshkian won Iran’s runoff elections to become the country’s next president. He won 16.3 million votes compared to 13.5 million won by his rival, Saeed Jalili. The elections came after his predecessor, Ebrahim Raisi, died in May in a helicopter crash.

The real power in Iran lies with Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. But while Khamenei sets the general direction for the country, the president directs policy on a day-to-day basis. Pezeshkian is now one of the Middle East’s main movers and shakers.

The odds seemed to be stacked against him. Of the six candidates Iran’s Guardian Council vetted to run for president, Pezeshkian was the only “reformist” among them. The others were Islamic hard-liners viewed by many analysts as Khamenei lapdogs. Some of Pezeshkian’s policy ideas are opposite of the way Raisi—and by extension, Khamenei—led the country. On June 25, Khamenei even publicly criticized Pezeshkian’s policies without naming him.

In a country where Khamenei can rig elections to his liking (as he did in 2009), Pezeshkian’s victory took many by surprise. Is this a turning point for Iran?

Who Is Masoud Pezeshkian?

Masoud Pezeshkian was born in 1954 in Mahabad, Iran, to an Azeri father and a Kurdish mother. He attended medical school and was a medic during the 1979–1989 Iran-Iraq War. He was Iran’s health minister from 2001 to 2005 under President Mohammad Khatami. Since 2008, he has been a member of Iran’s legislature. The 2024 election was his third attempt to enter the presidency.

Campaigning as a reformer, Pezeshkian has several major policies that differentiate him from Iran’s political establishment. While he supports Iran’s hijab laws, he believes the government has gone too far in enforcement. When Mahsa Amini died in police custody for violating the policy in 2022, he said, “It is unacceptable that in the Islamic Republic, a girl is arrested for her hijab and then her body is handed to her family.” During a July 1 debate, he claimed the government is losing legitimacy among Iranians “because of how we treat women.”

Pezeshkian also wants to reset Iran’s foreign relations. During Raisi’s administration, Iran moved closer to Russia and China. Iran is one of Russia’s biggest sponsors in its war on Ukraine. Raisi invited China to broker a normalization agreement with Saudi Arabia. Pezeshkian aims to continue reaching out to such powers. He had a phone call with Russian President Vladimir Putin on July 8, and the two “reaffirmed their commitment to closely work together” in “mutually beneficial cooperation.” They also agreed to visit each other soon.

But Pezeshkian also wants to open up to the West to free Iran from the West’s punishing economic sanctions.

The main force behind the sanctions is the United States. Warming up to the U.S. would require some distancing from Russia and China.

A New Nuclear Deal?

Many of Iran’s most crippling sanctions are tied to Iran’s rogue nuclear program. And perhaps most significantly, Pezeshkian said he hoped to renegotiate an agreement similar to the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (jcpoa).

His choice of staff suggests this is not election bluster. While campaigning, he got help from Mohammed Javad Zarif, foreign minister under former President Hassan Rouhani. Zarif publicly endorsed Pezeshkian’s foreign policy, appearing with him at campaign events and even on state television. It was under Zarif that the jcpoa came together with U.S. President Barack Obama’s team.

Tasnim News Agency, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ media outlet, reported on July 10 that Pezeshkian will name Abbas Araghchi as foreign minister. Araghchi was Zarif’s deputy foreign minister and the main negotiator for the jcpoa.

What Does This Mean?

The Guardian Council, a Khamenei-appointed body that has veto power over presidential candidates, usually lets at least one “reformer” run in elections to maintain the facade that Iran is a democracy. But its main purpose is to make sure nobody who could cause problems for Khamenei’s vision has a chance to be president.

It is possible the council approved Pezeshkian’s candidacy without realizing how popular he would be. Voter turnout was roughly 40 percent during the election’s first round between six candidates. It increased to roughly 50 percent when it was between Pezeshkian and Jalili. Between the regime’s bloody crackdown on hijab-less women and the escalating war with Israel, Iran’s current hard-line direction is unpopular with many on the street. Perhaps Khamenei let the people’s vote prevail this time so as not to rock the boat.

But in Iran, “reformists” are only relative. The Guardian Council would never have let Pezeshkian run if he could seriously jeopardize Khamenei’s agenda. Pezeshkian himself stated his job is to work policy as set by Khamenei’s general direction. For issues like the hijab law, Pezeshkian is not against them; he just doesn’t want the government to be too heavy-handed in enforcement. He has committed to continue supporting Russia, which would include help in the Russo-Ukrainian War.

As for Iran’s war on Israel, Pezeshkian has made no sign he plans to end it. He told journalists he wants “friendly relations with all countries except Israel.” According to a letter he sent to Hassan Nasrallah, leader of the Hezbollah terrorist group fighting in Israel’s north, Pezeshkian’s government will continue the war. “The Islamic Republic of Iran has always supported the resistance of the people in the region against the illegitimate Zionist regime,” he wrote. “Supporting the resistance is rooted in the fundamental policies of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the ideas of the late Imam [Ruhollah] Khomeini, and the guidance of the supreme leader, and will continue with strength.”

Pezeshkian is only a reformist in the same sense as Nikita Khrushchev, in the Soviet Union, was a reformist compared to Joseph Stalin. He may bare his teeth a little less than some of his colleagues. He may want to solve some of problems with diplomacy rather than Kalashnikovs. But it is still the same regime pursuing the same goals.

Also Khamenei couldn’t reset relations with the West without at least some sort of appearance of a change of direction. Pezeshkian’s election gives this appearance.

The Trump Factor

The United States’ presidential elections are in November. Joe Biden’s administration has been quite generous with Iran, not taking any meaningful steps to force Iran to back down in its terror war. It has given Iran billions of dollars in sanctions relief. It started secret nuclear negotiations that have apparently been put on ice since the October 7 massacre. But with Iran’s old nemesis Donald Trump soaring in popularity among the U.S. electorate, this generosity may dry up in a matter of months. The same administration that assassinated Gen. Qassem Suleimani and implemented “maximum pressure” sanctions is poised for a comeback.

Iran’s presidential candidates were very cognizant of this leading up to the vote. Before the first round finished, the six candidates were constantly marketing how they would be the right man to face down Trump. Biden was hardly mentioned. The New York Times summarized it best with its June 26 article: “Iran’s Presidential Candidates Agree on One Thing: Trump Is Coming.”

Khamenei may think a return to the jcpoa is likelier under Biden. Having Pezeshkian do the negotiating could bring a deal to the table before the election. Appointing Iran’s former chief nuclear negotiator as foreign minister shows how big of a priority this is.

Or perhaps Trump may want to negotiate his own deal as he and Zarif have indicated. Khamenei may want a fresh face in the presidency to get ready for this.

Either way, expect Iran to keep doing what it is doing.

The Future

The Trumpet watches Iran because of a prophecy in the book of Daniel. “And at the time of the end shall the king of the south push at him: and the king of the north shall come against him like a whirlwind, with chariots, and with horsemen, and with many ships; and he shall enter into the countries, and shall overflow and pass over” (Daniel 11:40).

This end-time prophecy leads to a global worldwide catastrophe (Daniel 12:1), and it starts with a “push”—a provocation—by a mysterious “king of the south.” For decades, the Trumpet has identified the king of the south as radical Islam led by Iran.

Because of this, we expect Iran to continue its ascent as “king” of the radical Islamist world. We expect Iran to keep pushing and provoking the West, including through its nuclear program. Verse 41 shows it will keep fighting over the “glorious land,” or the land of Israel. Verses 42-43 name countries that will ally with Iran, including Egypt, Libya and Ethiopia. Because of this, we expect Iran to keep adding to its proxy empire in the Middle East and Africa. Iran has already made great progress in all of these areas, but it hasn’t reached the Daniel 11:40 apex of power just yet.

Don’t expect Iran to change direction under its new leader. Expect Iran to double down on its trajectory. Pezeshkian might even be the man to hit the accelerator.

To learn more, request Trumpet editor in chief Gerald Flurry’s free booklet The King of the South.