Our Democratic Order Is Unraveling

By Richard Palmer and Joel Hilliker

Our Democratic Order Is Unraveling

Our Democratic Order Is Unraveling

By Richard Palmer and Joel Hilliker

Democracy is continually hailed as the ideal form of government. Even dictators like Vladimir Putin and Nicolás Maduro hold elections to pretend that they hold power by the will of their people. Kim Jung-un wraps himself in a cloak of legitimacy by calling his tyranny the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

In the United States, the political left are so intent on avoiding the danger that Donald Trump poses to “our democracy,” they have tried to impugn, impeach and imprison him—whatever is required to prevent him returning to power by popular (democratic) vote.

Political scientist Francis Fukuyama called democracy “the end-point of mankind’s ideological evolution.” He predicted “the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.” Internationally, it is hailed as humanity’s salvation. Another political scientist, Jack Levy, wrote that the “absence of war between democratic states comes as close as anything we have to an empirical law in international relations.” Spread democracy, and world peace flourishes.

By an odd coincidence, a couple of opinion polls have found that the same percentage of Americans—74 percent—believe in democracy as believe in God.

While the West still believes in democracy as an abstract principle, most are disappointed with it in practice. Only 10 percent of Americans say democracy is working very well or extremely well in the U.S. Nearly half say it is not working well. Just over half say that “people like you” are not represented by the government and that Congress is doing a bad job upholding democratic values.

What is the real problem? Is democracy flawed? Or does the problem lie within us?

Who Chooses the Choices?

Up until July, America seemed set for a Joe Biden vs. Donald Trump rematch. And the nation’s preferred candidate: neither. Forty-five percent of Americans said the match-up was bad for the country. Only 29 percent saw it as good.

This is not an American phenomenon. In Britain’s elections, held on July 4, both

left- and right-wing candidates had negative approval ratings. More voters said both are indecisive, untrustworthy and weak than those who described them with the opposite positive characteristics.

In a monarchy, a limited number of entitled members of the royal family have the chance to rule. But democracy has the entire talent of the nation to choose from. Why, in country after country, are people forced to choose between options that few want?

On July 21, after behind-the-scenes pressure from Barack Obama and others, Joe Biden announced that he would not seek reelection. Shortly afterward, Biden endorsed Vice President Kamala Harris to succeed him. But no voters chose Harris to run for president. Democrats will have to vote for a candidate nobody asked for. (And if President Trump hadn’t tilted his head at the moment he did, the same might have been true of Republicans as well.)

Clearly an election cannot be a contest among every adult in the country. A process is needed to pare down the options. And in country after country, that process has gone terribly wrong.

How Do You Vote?

A democracy has to present its citizens with choices and then tally up the votes. Seems simple enough. Yet here we meet more problems.

In 2019, Britain chose between Conservative candidate Boris Johnson and Labour candidate Jeremy Corbyn. A center-left leader would have had a good chance of winning that election. Yet somehow Labour had chosen an out-and-out Communist. Corbyn suffered a terrible defeat with barely more than 10 million votes and resigned in disgrace as the Conservatives swept to power in their best result since 1987.

This July, Labour’s vote share sank further: They barely eked out 9.7 million votes. Their support was down half a million voters compared to the 2019 election—but this time, astoundingly, they swept to power in a landslide. Winning fewer votes, they still won two thirds of the seats in Parliament.

Meanwhile, Reform UK, a brand-new party, had a very good year. They came in third place with 14.3 percent of the vote. This impressive figure won them 0.7 percent of the seats in Parliament. Another smaller party, the Liberal Democrats, won 11.6 percent of the vote—but won 14 times as many seats as Reform.

Is this really democracy?

Britain has a relatively simple voting system: first past the post. Each constituency holds a race. The person who finishes first may have received only 30 percent of the vote. But if his rivals each receive less than 30 percent, he wins. This election, the right-wing vote was split between the Conservative and Reform parties. In vote after vote, they came in second and third place. But across two thirds of the country, Labour came in first, handing them the majority.

First past the post is a relatively simple system. Perhaps a more complex system could solve the problem?

France also held elections around the same time, and its system is much more elaborate. If a candidate wins more than 50 percent of the vote, he takes a seat in the National Assembly. But if no one crosses that threshold, the candidates who got more than 12.5 percent of the vote go through to a second round.

This system is specifically designed to prevent what happened in Britain. If most voters want someone on the right, that vote may be split between several candidates in the first round. But they will come together in the second, uniting behind the most popular of their preferred candidates.

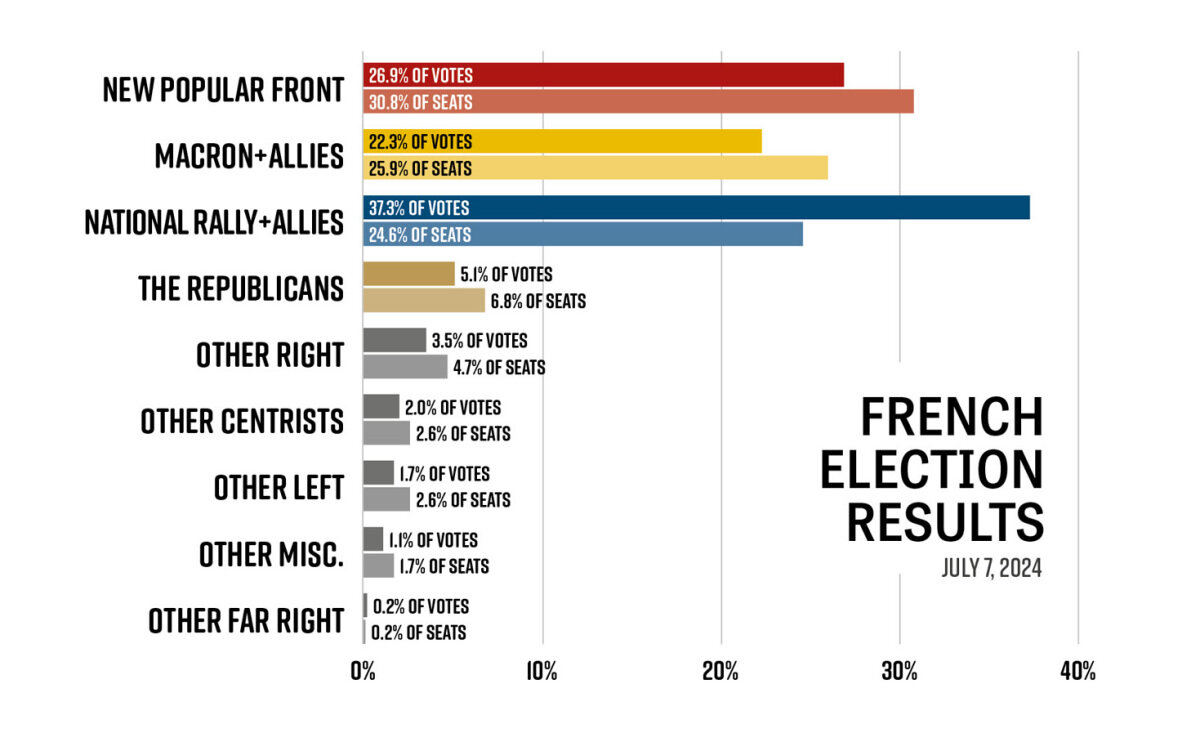

Elections for European Parliament were held across Europe June 6 to 9. In France, the far-right National Rally won a shock victory, winning 31 percent of the vote. President Emmanuel Macron’s party won half that. After this massive defeat, Macron called early national parliamentary elections, perhaps hoping moderate voters scared by the June results would vote in much more consequential national elections. But in round one, Macron’s bid to defeat National Rally failed. Once again it won, with just over 33 percent. Ipsos projected the National Rally would win between 230 and 280 seats out of 577.

Round two was held on July 7. Again National Rally increased its vote share and got more votes than any other party, with 37 percent of the vote. But in terms of seats in the Assembly, it came in third. The party that got the most seats was the New Popular Front—despite winning only 25 percent of the vote.

How did National Rally win first place in the popular vote but third in number of seats? Tactical voting. Members of the mainstream right and almost-mainstream left collaborated. In each race, if the right was best placed to win, the left withdrew its candidate—and vice versa.

France—the country of liberté, égalité, fraternité—now faces three choices: far right, far left or paralyzing gridlock (article, page 20).

Perhaps a different system would fix the problem? Award seats strictly in proportion to the number of votes each party receives: 10 percent of the vote gets you 10 percent of the seats. Simple and democratic, right?

The Netherlands runs its elections exactly this way. On July 2, Dick Schoof was inaugurated as prime minister. How many people voted for him? No one. He didn’t stand for election, led no party, and won no votes.

The Dutch held an election in November 2023. First-past-the-post systems discourage voting for smaller parties: A vote for a party polling around 5 percent is a vote wasted, as it will probably not get any seats in parliament. In the Netherlands, that is not case. In last year’s elections, the winning party, the pvv, had only 23.5 percent of the vote. Fifteen different parties won seats in parliament. It took four of the largest coming together to achieve a majority.

These four parties disagree on many fundamental issues and couldn’t agree on any party leader becoming prime minister. The only way they could form a government was to pick an outsider. Leaders and policies were decided not by voters but by backroom deals. After six months of talks, what finally emerged was a prime minister and political program that no one voted for.

Three very different election systems all produced the same result: something that’s not exactly democratic, and a government that most people did not vote for.

This is not a problem that a simple rearrangement of the system can fix. Every setup has downsides. Every system can be gamed by tactical voting. A system designed to give the people what they want fails at doing even that.

The History of Democracy

Democracy has a short, spotty history. Prior to modern times, only two significant states (which left detailed records) came close: the Greek city states and the Roman Republic. Yet neither was a democracy by modern standards. In Greece, only a handful of citizens could vote. Rome also disenfranchised many; the votes of the poor were worth less than those of the rich, and high birth carried enormous privilege. (Even in early America, only 10 to 20 percent of the adult population were eligible to vote.)

Nevertheless, the lesson is clear: In both Greece and Rome, the democracies were spectacular failures.

In the Greek civil wars between Athens and Sparta, the Athenians’ democracy made an utter muddle of its war efforts. Top military leaders were continually put on trial by their own people. Some fled or defected to avoid punishment. It was a war run incompetently by a committee of hundreds, ending in defeat by the authoritarian Spartans.

And this was hardly Athenian democracy’s only failure. It ultimately turned society into “a chaos of class violence, cultural decadence and moral degeneration,” historians Will and Ariel Durant wrote. It was “corroded with slavery, venality [bribery and corruption], and war.” They called democracy “the most difficult of all forms of government, since it requires the widest spread of intelligence, and we forgot to make ourselves intelligent when we made ourselves sovereign” (The Story of Civilization).

The Roman Republic succeeded where Athenian democracy failed: in the crucible of war. But in 133 b.c., it began to fall apart. Infighting among politicians resulted in the deaths of several prominent leaders. The republic descended into civil violence. Assassinations became common, then rebellions and uprisings. Around 60 b.c., Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (better known as Pompey), Marcus Licinius Crassus and Julius Caesar formed a private agreement to control the political process. This, according to Mary Beard, “for the first time effectively took public decisions into private hands. Through a series of behind-the-scenes arrangements, bribes and threats, they ensured that consulships and military commands went where they chose and that key decisions went their way” (SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome). The three men famously fell out, and civil war erupted. This time, the conflict would determine who would effectively become Rome’s first emperor: Caesar or Pompey. Democracy was already dead.

Modern Democracies

The founders of America did a remarkable thing: They pondered all history’s examples and sought to devise a government that would avoid the traps and troubles that have shipwrecked nations and empires. Most presciently, because of their education in the Bible they recognized that the real enemy of good governance and national longevity is human nature. Thus they sought above all to constrain this evil. They created a government with very limited powers, one that would afford the people an unmatched level of individual freedom and responsibility. They devised a system that harnessed the strength of a monarchy (in the president), elements of oligarchy (with state and national legislatures made up of representatives), and limited elements of democracy.

America’s founders were cautious in applying democratic elements. Only certain leaders were chosen by vote, at certain intervals. The extreme tendencies of the masses were filtered through an electoral college. Voting was restricted to men who were considered responsible and able to rightly exercise that power. Yet still, by historical standards it was a remarkably universal democracy.

This form of government has safeguarded unparalleled freedom and has released an outpouring of productivity and creativity. The founding principle of freedom was applied to trade as well, and the free market has helped to lift more people out of poverty than any other single force in history. This democratic experiment has proved especially long-lived and successful.

And yet, as inventive as the founders were in working to bridle human nature, human nature has proved itself far more inventive. The separation of powers, the checks and balances they established to limit the problems caused by a bad king—though they made America remarkably resilient despite some bad leaders—are increasingly being wielded as weapons for nakedly political purposes. In recent years, a shocking level of entrenched corruption within governing bodies has been and is being exposed, and the government is at absolute war within itself.

Beyond that, ultimately, democracy is subject to the same peril that monarchy is: An incompetent ruler can make life unlivable. In a democracy, the “ruler” is the people. The more wicked the people become, the more rapidly governmental and social stability turns to dust. And the more democratic a government, the more volatile.

As Herodotus said, “The mob is altogether devoid of knowledge.” People can be very foolish. They can vote for politicians who promise benefits at the expense of the national good. Besides racking up massive debts, this can mean neglecting areas of spending that don’t give immediate returns, such as defense. This weakness almost saw democracy wiped out in World War ii.

Enjoying broad freedom also gives human nature more room to stretch out. Far too often, people descend into excesses and evils. America’s founders knew that preserving freedom depended on the religion and morality of the people. Today, Americans have largely dismantled these pillars of society. We broadly celebrate perversions and sins that were barely imagined in previous generations.

Democracy may in fact be, as Churchill said, “the worst form of government, except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.” This is supposedly the peak of human achievement in governance, and it is a wreck! Few look at the political muddle in Washington today and see a system worth emulating. Many nations are surrendering freedom in favor of a single strongman—a 21st-century king.

For 6,000 years man has been writing these lessons in government, mostly through suffering and oppression—and by showing what does not work.

Why the Flaws

It’s not a coincidence that among the most prominent examples of modern democracies are the U.S. and Britain. Biblical and secular history reveal them as the descendants of ancient Israel—the fulfillment of God’s promise to Abraham to make of his descendants “a great nation” and “a company of nations” (Genesis 12:2; 35:11). (For proof of this, request a free copy of Herbert W. Armstrong’s book The United States and Britain in Prophecy.) Among these blessings was a comparatively just system of government.

Free government coupled with prosperity enabled God’s true Church and work to thrive. God ultimately fulfills His plan through His Church (e.g. Galatians 4:25-26). To His Church, God granted the Holy Spirit, the power that makes growth in real character possible (Romans 8:6-9). It is through the Holy Spirit that human nature is changed.

“Up to [the founding of ancient Israel], mankind had been denied spiritual knowledge and fulfillment from God,” Mr. Armstrong wrote in Mystery of the Ages. “God now decided to give them knowledge of His law—His kind of government—His way of life! He was going to prove to the world that without His Holy Spirit their minds were incapable of receiving and utilizing such knowledge of the true ways of life. He was going to demonstrate to them that the mind of man, with its one spirit, and without the addition of God’s Holy Spirit, could not have spiritual discernment—could not solve human problems, could not cure the evils that were besetting humanity. … [T]he intellectuals and scholarly of this world feel that, given sufficient knowledge, human carnal man could solve all problems. God let many generations of ancient [and modern] Israel and Judah prove by hundreds of years of human experience, that the best of humanity, without God’s Holy Spirit cannot solve human problems and evils!”

God raised up the nation of Israel to represent Him (Deuteronomy 4:7). And the great lesson God wants man to learn since the expulsion from the Garden of Eden is that not one human form of government apart from God, even if blessed by God despite itself, is going to bring utopia.

Democracy’s modern failure then is a sign that humanity is about to learn this lesson. Plenty more has to happen before the lesson becomes crystal clear. But God is letting society fall apart for a reason. Ultimately, this is also one step further in getting mankind to really know Him. Once that happens, God promises a government that will solve man’s problems, leading to the freedom that he craves.