Egypt on the Brink

Egypt on the Brink

I met a traveler from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, king of kings;

Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

—Percy Bysshe Shelley, “Ozymandias”

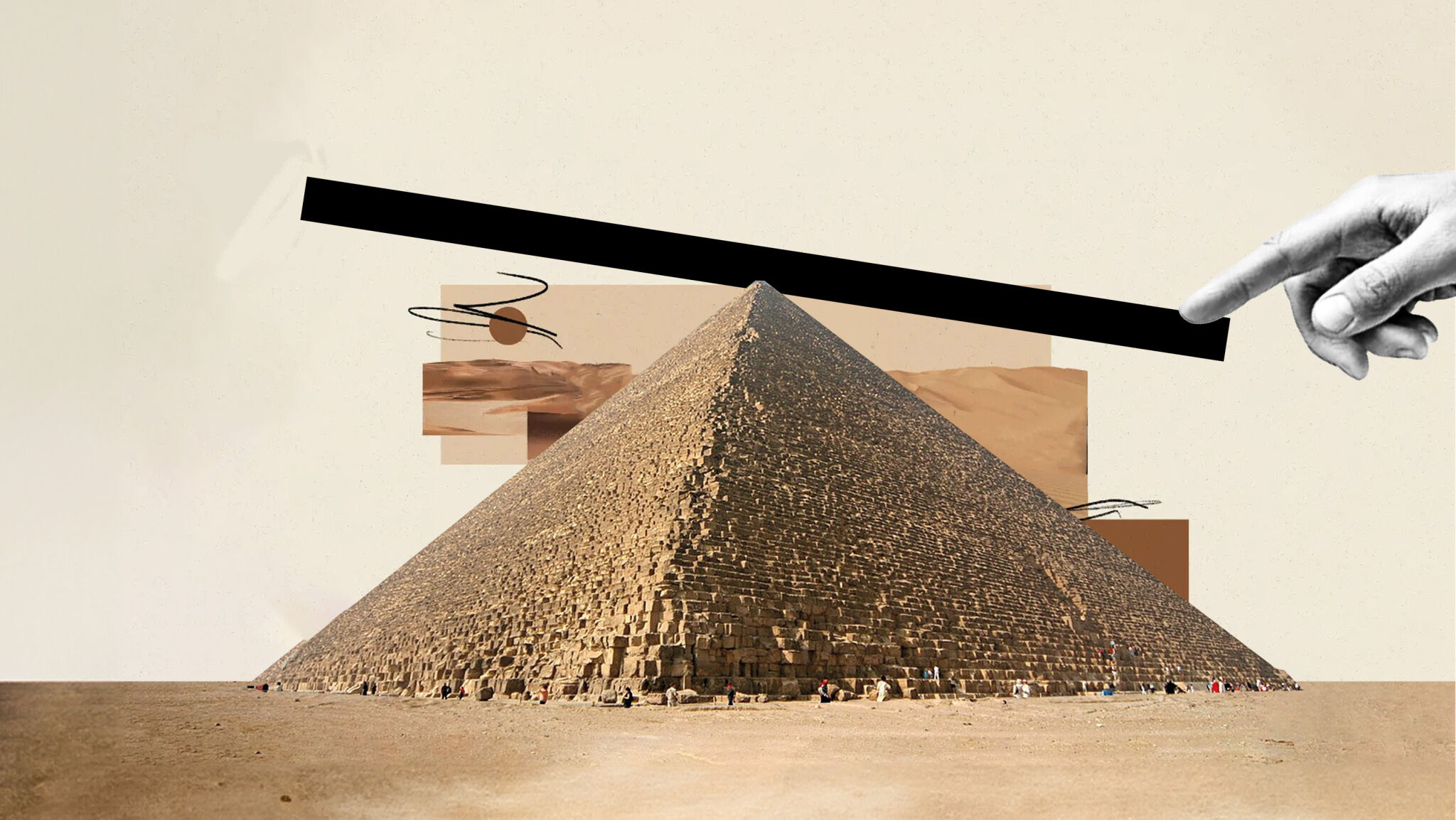

Shelley’s poem, describing the irredeemably crumbled empire of a boastful pharaoh, in a sense applies to Egypt today. Egyptian power today is decaying, and much faster than its current ruler, President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, would think or expect. He faces cascading economic crises that threaten to erase his legacy, from causes as varied as covid-19 to the Ukraine war to the Houthis. The Egyptian people today are demanding dramatic change.

Yet everyone remembers what happened the last time they felt this way and filled the streets of Cairo. When they get the change they are crying out for, not only the Middle East but every corner of the world will be impacted.

Close to 30 percent of Egypt’s 111 million people live in poverty. More than 70 percent rely on government-subsidized bread. The World Health Organization estimated in 2021 that more than 1 in 5 Egyptian children has stunted growth due to undernourishment. Egypt is the second-largest debtor state to the International Monetary Fund, owing the bank about $15 billion to keep its economy afloat.

In April, the imf estimated Egypt’s inflation rate—around 32.5 percent—to be the ninth-highest in the world, worse than those in Haiti and Bangladesh. The New York Times Cairo bureau chief gave a snapshot of living in such a volatile economy: “Grocery prices are stratospheric. Money is worth half of what it was a year ago. For many, eggs are now a luxury and meat is off the table. For others, burdened with school fees and medical expenses, the middle-class lives they had worked doggedly to sustain are slipping beyond their grasp” (Jan. 23, 2023).

One of Egypt’s economic lifelines is its history that draws tourists to contemplate it among such ruins as Shelley’s traveler described. Tourism accounts for an estimated 10 percent to 15 percent of Egypt’s economy and 10 percent of its jobs.

In 2019, Egypt received a record 13 million tourists. The following year, as coronavirus lockdowns swept the world, that number dropped precipitously to 3.6 million. Tourism revenue for the 2020–2021 fiscal year plunged nearly 70 percent.

Those numbers have rebounded, and once again close to 13 million people a year visit Egypt. But such a dramatic pause for so long in such an impoverished country has ripple effects. And it was not the only global event to rattle Egypt’s tourist industry and its overall economy.

The Heart That Fed

Before 2022, about a third of Egypt’s tourists came from two countries: Russia and Ukraine. When Russian President Vladimir Putin expanded his invasion of Ukraine into full-scale war in 2022, that source of tourists dried up. But Russia and Ukraine provide something even more valuable to Egypt than tourists: wheat.

The land around the Nile River is extremely fertile and has supported strong empires for thousands of years, but most of those empires didn’t have to feed 111 million people. The Egyptian government relies on massive amounts of food imports. In fact, it competes with China, which has about 12 times more mouths to feed, as the world’s biggest wheat importer. In 2022, Egypt imported $4.8 billion worth, close to 7 percent of world wheat exports.

One reason for Egypt’s heavy reliance on wheat is its bread subsidy program, which has existed for more than 100 years and currently provides five loaves per person per day. This amounts to almost 2 percent of government spending. In 2021, Russia was the world’s largest exporter of wheat, responsible for 17 percent of global exports. Ukraine, at 10 percent, was the fifth largest. Their productivity and relative proximity made them logical partners for Egypt. Both countries are still exporting wheat, but the shock waves of the war have caused bread prices to rise dramatically. Since 2022, Russia has disrupted Ukraine’s exports through the Black Sea to further its own goals. Last year, Russia backed out of a deal not to disrupt Ukrainian grain shipping from the Black Sea.

Russia admitted that it hoped this move would starve poorer nations. The idea was to force the world on threat of starvation to drop global sanctions against Russia. “All our hope is in the famine,” said Margarita Simonyan, editor in chief of Russia’s government-run RT news agency, in 2022. “[T]he famine will start now, and they will lift the sanctions and be friends with us because they will realize it is necessary.”

Russia caused this crisis to hurt not only Ukraine but also countries dependent on grain imports. Egypt is at the top of the list.

Ukraine resumed grain exports this year. The initial crisis is over. But as with the coronavirus, such a jolt to an already impoverished country struggling to feed its people will have lasting effects.

On June 1, the Egyptian government quadrupled the price of subsidized bread in a cost-saving measure. This reduces the strain on government funds and the economy, but it also turns many Egyptians against the government and Sisi. There are dangerous precedents for this in living memory. President Anwar Sadat tried to raise the price in 1977 but backed down after massive riots. One of the primary reasons over a million people packed into Cairo’s Tahrir Square to oust his successor, Hosni Mubarak, was unaffordable bread. Those 2011 protests led to Mubarak’s deposition and regime change.

2023 brought another crisis to Egypt—one that hit much closer to home.

Colossal Wreck

On Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas terrorists crossed from Gaza into Israel, murdered 1,195 people and abducted over 200 more. Israel retaliated by invading Gaza. While the world focuses on the war, the impact on Egypt is less apparent but incredibly consequential.

Hamas’s sponsor, Iran, activated another of its proxies in the war against Israel last November: The Houthi movement in Yemen began attacking commercial shipping in the Bab el-Mandeb strait, the Red Sea’s southern choke point.

Israel’s Red Sea port of Eilat has received less traffic due to the Houthis’ attacks. But Israel is not the Red Sea’s most vulnerable customer; that is Egypt. Egypt depends on the Suez Canal for much-needed foreign revenue. But when ships can’t pass through the Bab el-Mandeb, they have no reason to pass through Suez. Many Western shipping giants, even with American security guarantees, are taking the longer but safer route of sailing their ships entirely south of Africa.

On January 11, Suez Canal Authority head Osama Rabie claimed revenues for 2024 were already down 40 percent from the corresponding time last year. In May, Egypt’s revenue from the Suez Canal dropped 48 percent year over year from $648 million to $338 million.

For the 2022–2023 fiscal year, the Suez Canal contributed 2 percent of Egypt’s gross domestic product. While Israel progresses in its Gaza invasion, the Houthis and Iran’s other proxies say they won’t stop their campaigns until Israel backs down. With the war having just passed its one-year anniversary, the Houthis show no sign of relenting.

Sneer of Cold Command

How is Sisi responding to these economic and other crises? Surprisingly, by spending on what could be called pharaonic vanity projects, including building an entirely new capital city in the Sahara.

The official reason for moving the government out of Cairo, its capital for over a millennium, is to provide the government a headquarters away from a congested metropolitan area of over 22 million people. Some analysts suspect the real reason is protection from revolution, keeping Sisi away from the potentially rowdy crowds that overthrew former President Hosni Mubarak.

The expected final construction cost is $58 billion. The furnishings include the Cathedral of the Nativity of Christ for Egypt’s Coptic Christian minority—the largest cathedral in the Middle East. Its Iconic Tower skyscraper is the largest in Africa. The capital’s Grand Mosque is the second-largest in Africa. The Octagon, at about seven times the size of the Pentagon in the United States, is the largest military headquarters building in the world.

Sisi claims he hopes people will move en masse to the new capital. But with low-end apartments having an $80,000 price tag, life in the New Administrative Capital (nac) is out of reach for most Egyptians.

The nac isn’t Sisi’s only vanity project. The $1 billion Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza, yet to fully open, will be the largest archaeological museum in the world. The Rod El Farag Bridge, the world’s widest suspension bridge, was also built under Sisi’s watch. An $8 billion expansion of the Suez Canal, meanwhile, failed to bring any meaningful increase in revenue, even before the Houthis started their shooting spree.

These megaprojects create job opportunities and encourage foreign investment, but with an economy as battered as Egypt’s, is the extravagance and grandiosity really necessary? Does Egypt need to build the world’s largest defense headquarters when tens of millions of Egyptians can’t afford to buy bread? Most Egyptians know these projects aren’t about jump-starting the economy.

“None of this is for us,” Mohammed Mahmoud, a nac construction worker, told the New York Times in 2020. Mahmoud gestured at the marble-fronted cityscape he helped build, then pointed to a billboard featuring Sisi. “It’s for him.”

Nothing Beside Remains

Just looking at the facts on the ground, the immediate future of Egypt and its ruler are not apparent. But the Trumpet is watching for a certain outcome based on Bible prophecy. Some factors stand out. Egypt today is weak. Its economy is vulnerable. Many of the circumstances are outside of the government’s control; nonetheless, Egyptians are getting fed up with their government and want change. The same top-heavy extravagance that Sisi is indulging in stirred revolution against Hosni Mubarak in 2011. The Muslim Brotherhood emerged from the mess and a dictatorial Islamist government resulted. Sisi was the one who, in turn, overthrew it and turned Egypt back again to secularism, but the Trumpet forecasts that radical Islam will yet win out.

Daniel 11 records an end-time prophecy: “And at the time of the end shall the king of the south push at him: and the king of the north shall come against him like a whirlwind, with chariots, and with horsemen, and with many ships; and he shall enter into the countries, and shall overflow and pass over. He shall enter also into the glorious land, and many countries shall be overthrown: but these shall escape out of his hand, even Edom, and Moab, and the chief of the children of Ammon. He shall stretch forth his hand also upon the countries: and the land of Egypt shall not escape. But he shall have power over the treasures of gold and of silver, and over all the precious things of Egypt: and the Libyans and the Ethiopians shall be at his steps” (verses 40-43).

The “king of the south” is a modern power bloc with a provocative foreign policy aimed against the West. It has a proxy empire controlling large areas of the Middle East and Africa. Since the 1990s, Trumpet editor in chief Gerald Flurry has identified the king of the south as radical Islam, led by Iran. He writes in his free booklet The King of the South: “Egypt will be conquered or controlled by the king of the north [modern Europe; request a free copy of History and Prophecy of the Middle East for more information]. This clearly implies that Egypt will be allied with the king of the south.

“This prophecy indicates we are about to see a far-reaching change in Egyptian politics! We have been saying since 1994 that this would occur. Look at Egypt today, and you see the nation’s foreign policy and political orientation changing in a way that threatens to transform the entire region!”

Iran is the number one sponsor of terrorism in the Middle East. Hamas, the Houthis, Hezbollah, al-Shabaab and many other notorious terrorist groups receive funding, weapons and even orders from Iran. Through the Houthis especially, Iran has demonstrated great capacity to hurt Egypt through its proxy empire.

Radical Islam, led by Iran, will take over Egypt. This nation, suffering from a perfect storm of crises, is ripe for this revolution right now. When it happens, it will not be “just another political turnover in a Third World country far away from the West.” Egypt has one of the largest militaries in the Middle East. It directly borders Israel and is a relatively short boat ride from Europe. The Houthis have demonstrated how much damage world trade sustains when one end of the Red Sea gets closed off. What happens when both ends close?

The lesson of Shelley’s “Ozymandias” is that, no matter how proud, every emperor loses his glory in the end. Shelley implies that this fictional potentate’s fall from “king of kings” to his empire becoming “lone and level sands,” took generations. Egypt’s modern pharaoh will not have to wait that long to see his realm crumble.

But the major significance of Daniel 11 is not Egypt’s fall or radicalization, but what follows it. After a turbulent “time of trouble, such as never was since there was a nation even to that same time,” these events lead to the time when “thy people [the people of God] shall be delivered …” (Daniel 12:1). This means the Second Coming of Jesus Christ, and everything associated with it: the resurrection of the dead (verses 2-3), utopia for Egypt and for every nation (Isaiah 19:24-25), and the end of this age’s curses. This hope beyond the storm is the perspective most needed.