© Philadelphia Church of God, Part Two

© Philadelphia Church of God, Part Two

“We are pleased to announce that the Worldwide Church of God … has reached a successful conclusion in its lawsuit against the Philadelphia Church of God.”— Ralph Helge, Worldwide News, April 2003

While formulating a defense against our counterclaim, the wcg also had to prove how badly they had been “damaged” by our distribution of Mystery—a book we gave away for free; one that the wcg had distributed for free during Mr. Armstrong’s life, and now had a “Christian duty” to keep out of print. The bulk of evidence in this regard fell on the shoulders of a “forensic economist” named John Crissey, who had worked as an expert in numerous cases for Allan Browne’s law firm. According to Crissey’s Sept. 18, 2002, preliminary expert report, wcg had been denied “profits” totaling $3.84 million—$4.3 million with interest—by our distribution of nearly 100,000 copies of Mystery. He also calculated the future “losses” of wcg to be $3.3 million. All totaled, wcg would be seeking $7.63 million in damages at trial—just for Mystery of the Ages. (They would also be seeking millions of dollars in attorneys’ fees.)

Crissey based his findings on the fact that Mystery recipients gave more money than non-recipients of the book—never mind the fact that Mystery recipients might be more inclined to agree with the pcg’s overall message and work. What Crissey ignored was that pre-1997 data showed that Mystery recipients had already been giving at a higher rate long before pcg even started distributing the book! He ignored this data (which we supplied him) because it completely contradicted his “expert” analysis. Many of our own members and their children were the first ones to request copies of Mystery once we began distribution. These people were already “pre-disposed” to giving more—they were already tithing members of the church!

In pcg’s motion to dismiss Crissey’s report, Mark Helm argued that the court should not admit Crissey’s testimony, calling it bogus, fatally flawed and defective junk science, among other things.

Judge Snyder agreed. She wrote in her tentative order, a few days after a November 25 hearing, “[T]he methodology employed by Mr. Crissey has not been shown to be sufficiently reliable to allow it to be presented to the trier of fact, and therefore his quantitative estimate of the amount of contributions that are attributable to distribution of moa is not admissible.”

Thus, on the eve of the damages trial, the wcg was faced with the prospect of not having any real evidence to show how much they were “damaged” by our Mystery distribution. Of course, they had much difficulty with this argument long before Crissey came along.

When we started distributing the work in 1997, we absorbed all the printing and mailing costs, and then gave it away free of charge. Under any circumstances, it would be difficult to show how this was some sort of moneymaking scheme for pcg. But for wcg to then claim that our free distribution was actually stealing “profits” from them is the height of hypocrisy. Aside from the unfathomable logic of the idea to begin with, why would they now seek “profits” from a book they had been ridiculing for years and had vowed to keep out of circulation?

The Cult “Expert”

Besides John Crissey, the wcg relied on other biased “experts” like Ruth Tucker, the self-proclaimed authority on “cultic movements.” Of course, when we brought up Tkachism’s personal beliefs, like during the Schnippert deposition, the wcg legal team would blow a gasket. But when they brought up our personal beliefs and tried to make us look like a dangerous cult, to them it was completely relevant to the merits of the case.

Tucker’s report was a boring rehash of what Tkachism had been saying all along. Mr. Armstrong was a dictator with bizarre teachings; Mystery of the Ages was a huge money-making scheme; the Tkaches courageously transformed the church; Gerald Flurry thinks he’s above the law, and so on.

Tucker said our claim that Mr. Armstrong wanted every prospective member to read Mystery of the Ages before baptism had “absolutely no merit at all,” even though the requirement was clearly stated in the Pastor General’s Report in 1986. Relying instead on page 26 of Transformed by Truth, Tucker said Mr. Armstrong’s baptismal requirements were, if anything, “lax.” She also said “there is no evidence that the pcg ever had a baptismal prerequisite” for reading Mystery, even though we had stated the policy verbally and in print numerous times between 1989 and 1996.

On the point of government, Tucker said Mr. Armstrong “was an authoritarian leader. His personality and leadership style dominated the wcg for five decades ….” In an article she wrote for Christianity Today in 1996, she characterized the wcg as a “classic case study of an authoritarian cult.” Mr. Armstrong, she wrote, “held tight reins over his diverse empire. His authority was unquestioned by most church members ….”

So at her deposition, we asked if she believed Mr. Tkach Sr. had inherited the same degree of control from Mr. Armstrong in 1986. She confidently said no, even though Feazell and Schnippert had both said the opposite earlier at their depositions. We told Tucker about how Tkach Sr. designated himself as an apostle in 1986 and about Tkach Jr.’s empty promises to modify the church’s form of governance—and she started backpedaling: “I’m not an expert in the area of church government.” But mention Herbert Armstrong or Gerald Flurry and she immediately becomes one.

Tucker wrote, “Former members of the pcg have told how Mr. Flurry’s words were often presented as the very words of God.” We asked about the identity of these “former members,” but she couldn’t remember which website she got it from. She assured us that “there are a number of sites that have postings from former members of the Philadelphia Church of God.” She did not, however, personally contact any current or former members of the pcg, nor any pcg officials, while preparing her “expert” testimony about our church.

Regarding our supporters, she said the people attracted to Mr. Armstrong’s teachings are book readers. “They might not be terribly sophisticated thinkers, but they were certainly people that read books ….” That’s how she characterizes hundreds of thousands of members who joined the wcg over the course of Mr. Armstrong’s ministry and millions more who read his literature and donated to his work—they’re all simple-minded.

Far from being hired for her expert testimony, Ruth Tucker was brought in because she is pre-programmed to heap praise on Tkachism no matter what. Her intimate relationship with the Tkaches goes way back. In 1988—two years after Mr. Armstrong died—Michael Snyder, the wcg’s assistant public relations director, contacted her about the doctrinal reforms taking place in the wcg. He wanted her to have the most up-to-date information for a book she was writing about cults. In 1991, Tucker invited Snyder’s boss, David Hulme, to speak at the Trinity Evangelical Divinity School about the progress the wcg had made in accepting the trinity doctrine. In 1996, the wcg returned the favor and invited Tucker to speak at its ministerial conferences. “Dr. Tucker was excited about our reforms and encouraged us in every way she could,” Tkach Jr. wrote in 1997. “We consider her a gift from God.”

Gutting Their Case

Judging by Ruth Tucker’s expert report, Mike Feazell’s preface and questions we were asked during our depositions, the wcg clearly intended to label us as a cult in court. They wanted to show how we were supposedly a racially bigoted, misogynistic fringe group, led by a self-proclaimed dictator.

But in her tentative order after the November 25 hearing, Judge Snyder said she would not allow the trial to turn into an “attack on Flurry” because it would “distract the jury from the issues at trial” and “unfairly prejudice pcg.” Later, the court concluded that the “wcg should not be permitted to describe specific religious tenets—either its own, or pcg’s—regarding racial issues because such evidence will be unfairly prejudicial and will confuse the issues at trial.” In explaining why they discontinued Mystery, the judge said she would allow wcg to say that it considered its message to be “no longer socially acceptable.” But so far as the judge was concerned, they couldn’t even use the word “race.”

Another huge breakthrough for us. Added to the ruling on Crissey, we felt the tentative order would pretty much gut the wcg’s case for damages. Not only were they unable to prove damages, now they couldn’t sling mud. Added to that, they still had to tackle our counterclaim, not to mention subject themselves to a rigorous pcg defense dead set on exposing their lies and deceit.

Sealing the Deal

The damages trial had now been pushed back to March 4, allowing both sides more time to argue over what evidence would be allowed at trial. At a December 18 hearing, as a follow-up to her tentative order, the judge said she wasn’t inclined to change her tentative ruling.

Two days after that hearing, the wcg seemed all the more eager to settle, lowering its licensing offer to a $3 million bottom line. Sensing desperation on their part, my dad was inclined to be patient. On December 24, we put together a $2.5 million package offer for all the copyrights to the 19 works involved in the litigation.

We didn’t hear back from wcg, despite their insistence to get things done quickly, until after their executives returned from their Christmas/New Year’s holiday celebration.

On Tuesday, January 7, the wcg came down to $2.8 million for perpetual licenses, but with these added concessions: The copyright notice, agreed upon by both sides before finalizing the deal, would say something like “© Publishing Inc.,” but we would not have to print any disclaimers under the copyright.

But buying the copyrights altogether, at a price range this “low,” was not possible, they told us. Their offer intrigued us: no disclaimer and a copyright notice that was at least inoffensive. For the most part, that’s what we had at the beginning of our distribution in 1997. We printed the works without a disclaimer and a notice that read “© Herbert W. Armstrong.”

In weighing their offer, we took a step back and considered our ultimate objective at the outset of our distribution of Mr. Armstrong’s works. It was to keep the wcg from destroying those writings forever by making them freely available to all who valued them. With that in mind, we began to see a scenario in which we actually could live with a license.

After weighing our options for several days, we reached a final decision on Monday, Jan. 13, 2003: $2.65 million for the wcg to “grant pcg a worldwide, nonexclusive, perpetual, irrevocable, fully paid-up, non-royalty-bearing license” to all 19 works. Under the agreement, the copyright notice would read “© Herbert W. Armstrong.”

The next day, to our utter amazement and shock, the wcg asked us to submit an alternative offer for buying the copyrights outright. Thus, by the end of the 14th, we had two final offers on the table—one for licenses and one for full copyright ownership. We offered $2.65 million for perpetual licenses and $3 million to buy everything outright.

On Thursday morning, January 16—17 years to the day after Herbert W. Armstrong’s death—the wcg agreed to sell us all the copyrights for $3 million. Apart from contributions from our insurance carrier, the total cost to the pcg was an even $2 million. With about $1 million on hand, we planned to finance the other $1 million.

Later that day, Mark Helm and the wcg’s attorney conference-called Judge Snyder to tell her that both sides had agreed to terms of settlement. Thus, for all intents and purposes, six years of litigation ended the afternoon of Jan. 16, 2003.

WCG’s “Successful” Conclusion

After settlement, Ralph Helge wrote to the members of the wcg, “We are pleased to announce that the Worldwide Church of God … has reached a successful conclusion in its lawsuit against the Philadelphia Church of God.” This is how he spun the negotiation process: “During the last year or so, pcg made different offers to license or purchase some or all of the literary works in question, and thereby settle the litigation. As the church did not consider that the amounts offered were sufficient, the offers were rejected. But then pcg made a substantial offer of $3 million to purchase 19 of the literary works written by Mr. Armstrong, and settle the litigation.”

That version of the story, as is customary with Tkachism, leaves out all the essential facts. But it didn’t matter to us. We knew that deep in his heart of hearts, Helge knew who came out victorious in this case.

Think about it.

Their publicly stated goal, from the very beginning of the battle, was to keep Mr. Armstrong’s teachings out of circulation. Joe Jr. had to eat those words.

They told the court early on that they had suffered irreparable harm by our “unlawful” action because in distributing Mystery of the Ages, we were “perpetuating beliefs no longer followed by Worldwide Church.” They loathed the thought of Mr. Armstrong’s teachings resurfacing.

The wcg owned the copyrights, Greg Albrecht said in 1997, and they “do not allow others to publish our former teachings and doctrines for a variety of reasons.” Flurry understood, they told the court in 1999, that the wcg “refused” requests to reprint Mystery of the Ages. This was common knowledge. They refused to make Mr. Armstrong’s works available—and they wouldn’t allow others to do it either.

After Judge Letts ruled that we could rightfully distribute Mystery of the Ages, Helge called the judgment an “erroneous view of the law” and said our reprinting was “in violation of both the commandment of God and the copyright law of the United States.”

They brought up the annotated plan in an attempt to overturn Judge Letts’s decision. After that happened at the Ninth Circuit, Helge said we only had “certain limited rights.” But for all practical purposes, he continued, the Ninth Circuit’s decision “would seem to be final in all material respects.” That, as it turns out, was wishful thinking.

Then, in April 2001, Tkach Jr. told Christianity Today that if the Supreme Court refused to hear our appeal, “wcg lawyers will go after several overseas websites that post the complete text of Mystery of the Ages.“ Intimidating words!

After the Supreme Court decided it would not hear our appeal, Ralph Helge’s assistant, Earle Reese, incorrectly asserted, “This is the end of the pcg’s ability to appeal to a higher court.”

After that, the wcg worked to make the literature available through print on demand. Not because they wanted to—they had to. But they still had the upper hand, they were convinced, because all the literature downloaded would include a nasty preface. Yet this turned out to be yet another stronghold position they gave up on.

Then, when asked about the likelihood of licensing Mr. Armstrong’s works to a potentially dangerous sociopath like my father, Joseph Tkach Jr. testified to this: The wcg had to be in a position where it could “police or control” the literature if there was to ever be a settlement in terms of licensing. More words they would have to eat.

And what about Helge’s letter to Bob Ardis, where he portrayed my father as a stiff-necked rebel attempting to thwart the legal process? We were completely out of options, he said. We were staggering along, acting on sheer desperation, but with no place to go, except before the bar of justice to be judged guilty and sentenced to pay up to the Worldwide Church of God. Of course, none of that ever happened either.

What did happen is this: They sold us a storehouse of literature for an amount of money that, by our estimate, barely covered their legal costs, if even that. They retrieved no “profits” or “damages” from us. All their “overwhelming” victories in court were conditioned on them making Mr. Armstrong’s works available. And in the end, they were exactly where they started before the case, money-wise, but having forfeited ownership of all 19 copyrights.

Ethical Questions

Writing in Christianity Today after the lawsuit settled, Marshall Allen said, “At one point, the wcg said it was fighting the countersuit because it didn’t want to see the heretical works republished.” But the church had since reversed its course, he wrote. Allen quoted Reginald Killingley, a former wcg pastor, as saying, “They’re willing, in effect, to support what they condemn—to permit the perpetuation and promotion of heresy for the sake of money.”

The article sent shock waves through the wcg, even prompting a response in the Worldwide News. The last thing the wcg wanted from this whole ordeal was for their friends in the evangelical community to turn on them. Christianity Today had long been a staunch supporter of Tkachism.

In its coverage of the lawsuit in 2001, the magazine summarized the case this way: “[T]he Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled on a 2-1 vote that Armstrong legally willed his copyright of Mystery of the Ages to the wcg, which could restrict its distribution. The court majority said that despite the wcg action to suppress the book, pcg could not claim fair use in reprinting the entire book. Because they now believe Mystery of the Ages is ‘riddled with error,’ wcg officials say they feel a Christian duty to withhold the book.” Believing many of the same doctrines Tkachism accepted, Christianity Today had no problem reporting on what they viewed as the wcg’s attempt to “withhold the book.” They didn’t want the book in circulation either!

So when the wcg granted us unrestricted ownership of all the copyrights, you can see why they were disturbed by the wcg’s about-face.

The wcg surrender also bothered another Tkachism advocate, Philip Arnn. Writing for Watchman Expositor in 1993, Arnn said, “The current doctrinal revisions being brought about by the efforts of Joseph Tkach and his team are to be applauded as extraordinary in light of their spiritual benefits to the church membership.” But their decision to sell the copyrights 10 years later, according to Arnn, raised ethical questions about the wcg. “These are heretical doctrines that are destructive to the eternal life of anyone who comes under their influence,” Arnn said. “To have profited from the release of the copyrights is a matter that I would think [would be] very troubling to the conscience.”

Even the wcg’s hometown newspaper, the Pasadena Star-News, called into question the church’s ethical standing. “The settlement … allows Armstrong’s followers in the Philadelphia Church of God to reproduce the books. … Present Pastor General Joseph Tkach Jr., however, once wrote that it was their ‘Christian duty’ to keep the book out of print ‘because we believe Mr. Armstrong’s doctrinal errors are better left out of circulation.’” The lawsuit had finally ended. It had been six years since Tkach Jr. wrote his book. And here he was still getting pummeled for the “Christian duty” statement—and from a newspaper in his own backyard!

According to the Star-News, Bernie Schnippert said it would have been financially “imprudent” for them not to accept the settlement offer. “We came to an end where we received a considerable sum of money and the other party received a number of works that are out of date and inaccurate according to most of the Christian world,” said Schnippert.

Just nine months earlier, we listened to Schnippert testify smugly that Tkachism had supposedly taken the moral high ground by not milking revenue from teachings they didn’t believe in—which is precisely what they did in the end.

To the Victor Go the Spoils

Contrast the wcg’s sellout with what the Philadelphia Church of God obtained in this struggle. Our one goal at the outset, stated clearly in all our literature, was to make Mystery of the Ages available to a wide audience. In the end—something we could not have imagined in our wildest dreams before the case—we owned Mystery of the Ages, as well as six other books by Mr. Armstrong, 11 booklets and a 58-lesson Bible correspondence course.

On top of the literature, we obtained access to thousands of internal documents through discovery—letters, reports, bulletins, interoffice memos, board minutes, e-mails, interviews, books, magazines, newspapers, sermons, announcements, transcripts, financial disclosures, contracts, surveys, spreadsheets and statistics. We obtained multiple thousands of pages of sworn testimony in affidavits, declarations and depositions. There was six years’ worth of court documents that we and the wcg had filed—briefs, rebuttals, motions, opposition motions, petitions, claims and counterclaims. Add to that all the documents filed by the judicial branch—courtroom transcripts, orders, tentative orders, summary judgments, injunctions, opinions and dissenting opinions.

Without these documents, it would not have been possible to write this book. And without this book, we could not have exposed Tkachism’s deceptive agenda nearly to the extent that we now have.

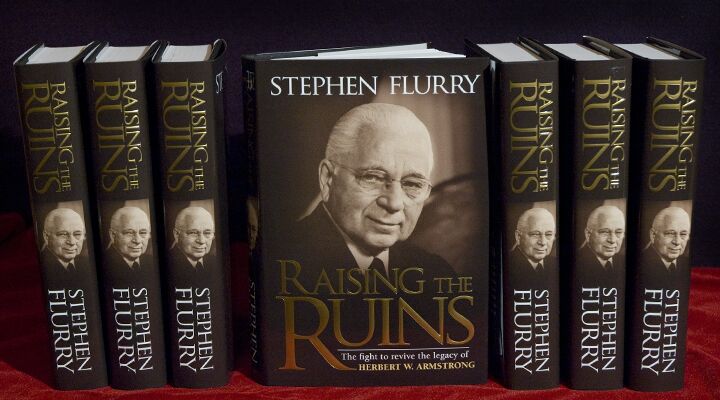

Besides Raising the Ruins, we had the opportunity to expose their lies during litigation—before judges, magistrates, attorneys, clerks, law students, reporters—even the general public. This case, after all, did attract national attention, including a feature story on the front page of the Wall Street Journal.

Then there were the depositions—particularly those during the summer of 2002. What an opportunity for a little “peanut shell” supposedly going nowhere. After the Tkaches absolutely wrecked the church we loved, we found ourselves in the enviable position of making them, under oath, answer for all they had done.

For their predisposed hatred for Mr. Armstrong and their slanderous assassination of his character.

For all the lies they told to the membership.

For the ministers they bullied or fired.

The selfish will they forced upon an unsuspecting flock.

For the reputations they destroyed.

The marriages and families they split apart.

For the work, the property, the publications and programs they either sold off or discontinued.

For their inept mismanagement of all the money and resources they inherited.

And for their self-righteous arrogance. A Christian duty to keep Mr. Armstrong’s doctrines “out of circulation”? I mean, really, who do they think they are?

They hated answering for all this. And the fact that we were in the same room, giving our attorneys suggestions and input along the way, made it that much more awkward and upsetting for them. In fact, at the very first deposition we had in the case, in the summer of 1998, their attorney objected to the fact that we had three pcg representatives in attendance—my father, Dennis Leap and me.

They wanted to strip away all the historical intrigue—the passionate spiritual and emotional involvement we had invested in this case, in this way of life under Mr. Armstrong. They knew we were righteously indignant—even angry—about what Tkachism had done. They knew we would intensely fight for our spiritual livelihood—so they didn’t want us around. They wanted this battle to be fought between lawyers only—and over what they considered to be purely a legal matter involving the Copyright Act and “stolen” property. But we insisted on being there for all of it. And we were. All three of us attended every major deposition—sometimes we even brought a fourth representative from our church. And besides the first hearing with Judge Letts, we attended every major hearing after that, even though it meant frequent flights between Oklahoma and California.

If they couldn’t prevent our attendance, they worked to prevent us from saying anything about the lawsuit. Early on, they designated just about everything as confidential. They didn’t want their story going public which, in itself, is a story. We, on the other hand, wanted complete transparency, which is why we later moved to have the confidentiality seal removed. I’m not saying we weren’t nervous when they deposed us. But we had nothing to hide. Our position was clear from the start. Yes, we printed Mr. Armstrong’s works—and we firmly believe, before God and the authorities of our land, that it was lawful. Besides that, we looked upon being deposed as if we were testifying on behalf of Herbert W. Armstrong’s legacy. What an honor.

There were many other moments we were proud of during our six-year struggle: The miraculous start to the case, when Judge Letts whipped the wcg into a tailspin, essentially saying, “I think you are going to lose.” Then at the Ninth Circuit, even though we lost, to appear in court a few blocks from the Pasadena headquarters Mr. Armstrong built—it was a privileged opportunity I’ll never, ever forget. I’m proud of the fact that we submitted a petition to the United States Supreme Court, even though it didn’t hear the case.

Besides all the proud moments, there were the many profound lessons we learned: the unwavering faith of my father; the willingness to stand up and fight for a worthy cause and the abundant fruit that came from that; how we must go on the offensive to overcome evil—like printing Mystery of the Ages irrespective of what they might do, or filing the counterclaim, or kicking off the ad campaign, or our response to the preface.

These all were powerful lessons I will never forget. What an education. I think of the many sermons and articles our struggle has already inspired—and now this book.

None of this would have happened without the lawsuit.

Honestly, I find it difficult to pinpoint anything negative about the litigation. Naturally, no one wants to be sued, but even in the midst of the litigation, our work prospered. Four out of the six years, we were able to freely distribute Mystery of the Ages to 100,000 recipients. For two years during the lawsuit, we freely distributed five other works by Mr. Armstrong.

Even looking at it financially, it was a blessing. Jesus likened the Kingdom of God to a pearl of great price. Upon finding that “pearl,” it says in Matthew 13, the merchant went and sold everything he had to obtain it. In Matthew 19, Jesus told a rich man who wanted to inherit the spiritual riches of God’s Kingdom that he had to be willing to give up everything of physical value.

Over the course of six years, including the $2 million we were responsible for at settlement, we spent about $5 million on this lawsuit—less than one tenth of our total income during this same period.

And considering what we obtained in return—it’s by far the best money we’ve ever spent.