Man vs. God: Debate Becomes Consensus

“The most highly educated,” wrote the late Herbert W. Armstrong, “view all things through the eyeglasses of evolutionary theory. … That is why the most highly educated are, overall, the most ignorant—they are confined to knowledge of the material, and to ‘good’ on the self-centered level. Knowledge of God and the things of God are foolishness to them.”

A recent issue of the Wall Street Journal featured a discussion between prominent thinkers on the subjects of evolution, science and the role of religion which proves the accuracy of Mr. Armstrong’s statement.

The feature, titled “Man vs. God,” is far from the debate one might expect between a professing theologian and an evolutionary scientist. Instead, both parties heartily endorse evolutionary theory and share an overt hostility to the idea of a sentient Creator.

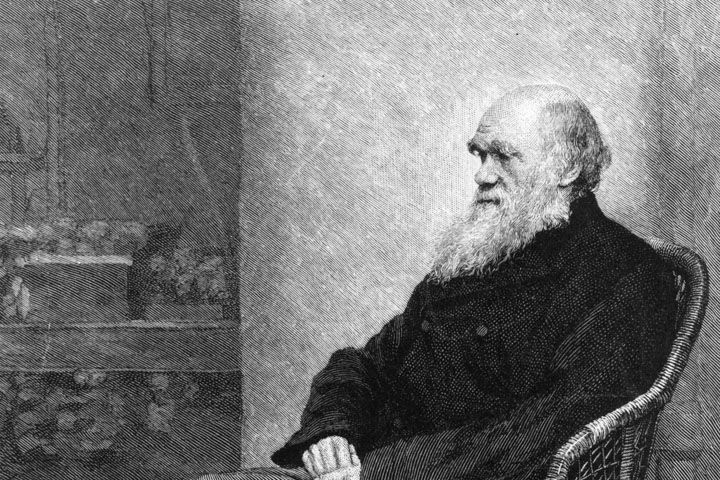

One essay is presented by author Richard Dawkins, widely acclaimed for his scathing denouncements of creationism in such books as The God Delusion. Predictably, he makes an empty case for the logic of Darwinian evolution to explain the origins of life.

Dawkins first dismisses the possibility of the universe having been created by a superior Being, using the following circular reasoning:

Making the universe is the one thing no intelligence, however superhuman, could do, because an intelligence is complex—statistically improbable —and therefore had to emerge, by gradual degrees, from simpler beginnings: from a lifeless universe—the miracle-free zone that is physics.

In other words, an intelligent Creator could not have made the universe, because such a sophisticated Being would first have had to evolve from a lifeless universe. Irrefutable logic! The questions of how the universe and the laws precisely governing it did indeed first come into existence are conveniently ignored.

Later, Dawkins seals up his case for Darwinian evolution, lavishing it with praise as “the only process we know that is ultimately capable of generating anything as complicated as creative intelligences. Once it has done so, of course, those intelligences can create other complex things: works of art and music, advanced technology, computers, the Internet and who knows what in the future?”

And where does this blind force of evolution leave God? Dawkins dutifully covers this as well:

The kindest thing to say is that it leaves Him with nothing to do, and no achievements that might attract our praise, our worship or our fear. Evolution is God’s redundancy notice, his pink slip. But we have to go further. A complex creative intelligence with nothing to do is not just redundant. A divine designer is all but ruled out by the consideration that He must [be] at least as complex as the entities He was wheeled out to explain. God is not dead. He was never alive in the first place.

Presented by a professing theologian, we might expect the accompanying essay to offer some rebuttal to Dawkins’s zealous appeal for the Darwinian faith. Quite the opposite. Prominent spiritual author Karen Armstrong begins by paying homage to evolutionary theory as a source of enlightenment for the modern notion of God:

But Darwin may have done religion—and God—a favor by revealing a flaw in modern Western faith. Despite our scientific and technological brilliance, our understanding of God is often remarkably undeveloped—even primitive.

And why so primitive?

In the pedantic language of scholarship, Karen Armstrong argues that the greatest flaw in modern religion is the belief that God exists in the literal sense. Echoing her rival essayist, she suggests that science has ruled out any possibility of a divine Creator. Religion, therefore, was in a purer form before anyone suggested the existence of God ought to be grounded in hard fact and science:

Religion was not supposed to provide explanations that lay within the competence of reason but to help us live creatively with realities for which there are no easy solutions and find an interior haven of peace; today, however, many have opted for unsustainable certainty instead. But can we respond religiously to evolutionary theory? Can we use it to recover a more authentic notion of God?

This “more authentic notion of God” is, of course, one who does not actually exist, but who is merely an ethereal symbol representing some fuzzy, spiritual philosophy. She summarizes this more sophisticated, modern theology as follows:

The best theology is a spiritual exercise, akin to poetry. Religion is not an exact science but a kind of art form that, like music or painting, introduces us to a mode of knowledge that is different from the purely rational and which cannot easily be put into words. At its best, it holds us in an attitude of wonder, which is, perhaps, not unlike the awe that Mr. Dawkins experiences—and has helped me to appreciate—when he contemplates the marvels of natural selection.

So according to this renowned theologian and spiritual author, God and religion have their valued place in a modern, enlightened society, so long as no “believers” fall prey to the delusion that God actually exists.

Ironically, it’s the unabashedly God-denouncing Dawkins who offers the only statement of truthful insight to be extracted from either of these essays. In a jab at modern theology’s absurd presentation of atheism as a belief in God, he concludes his argument as follows:

Now, there is a certain class of sophisticated modern theologian who will say something like this: “[O]f course we are not so naive or simplistic as to care whether God exists. Existence is such a 19th-century preoccupation! It doesn’t matter whether God exists in a scientific sense. What matters is whether He exists for you or for me. If God is real for you, who cares whether science has made him redundant? Such arrogance! Such elitism.”

Well, if that’s what floats your canoe, you’ll be paddling it up a very lonely creek. The mainstream belief of the world’s peoples is very clear. They believe in God, and that means they believe He exists in objective reality, just as surely as the Rock of Gibraltar exists. If sophisticated theologians or postmodern relativists think they are rescuing God from the redundancy scrap heap by downplaying the importance of existence, they should think again. Tell the congregation of a church or mosque that existence is too vulgar an attribute to fasten onto their God, and they will brand you an atheist. They’ll be right.

With these two authors in such harmony in their ridicule of creationism, it seems the intent of this Wall Street Journal feature is to suggest that, among intelligent, objectively thinking scholars, there simply is no debate; belief in a Creator God has long-since been established as primitive superstition. The only thing left to debate is whether retaining the word “God” might be of some use in modern atheistic philosophy.

Discussion or debate of any alternative to evolutionary theory, however grounded in objective fact, is academic heresy, and would presumably invite ridicule from the sophisticated Wall Street Journal readership.

Why such hostility toward authentic debate on the subject of creation?

The prominent theologian sharing the name Armstrong, who was quoted at the beginning of this article, answered this question. Herbert W. Armstrong wrote extensively on fundamental flaws of modern scholarly thought. “The most highly educated,” he stated in his magnum opus Mystery of the Ages, “view all things through the eyeglasses of evolutionary theory.”

Mr. Armstrong continued:

Evolution is concerned solely with material life and development. It knows and teaches nothing about spiritual life and problems, and all the evils in the world are spiritual in nature.

That is why the most highly educated are, overall, the most ignorant—they are confined to knowledge of the material, and to “good” on the self-centered level. Knowledge of God and the things of God are foolishness to them. But, of course, God says, “The wisdom of this world is foolishness with God” (1 Corinthians 3:19).

What a telling example this Wall Street Journal feature presents of the blinding force of intellectual pride in what is put forward as a fair-minded examination of factual merits of both sides of the coin.

For more on the blindness of intellectual vanity, read the Trumpet reprint of Mr. Armstrong’s Plain Truth magazine article “Higher Learning?”